Working at the intersection of health and business in Uganda

Liana Wang, Yale College Class of 2020, is currently in Uganda working with Living Goods as part of the Market Solutions for Inclusive Societies class she is taking with Professor Bo Hopkins (see related story). The following is an excerpt from one of the reports she has written about her experience there.

A hot afternoon had melted into cool evening air, yet dozens of women still sat waiting on the grass before their sub-county headquarters in Buyengo, a rural region outside of Jinja, Uganda. I was there with fellow students, Simon and Nadira, to shadow a team at Living Goods, a non-profit pitching itself at the intersection of health and business. It identifies and trains women in largely rural areas to become community health providers (CHPs), who form the frontline for maternal and child health in their villages.

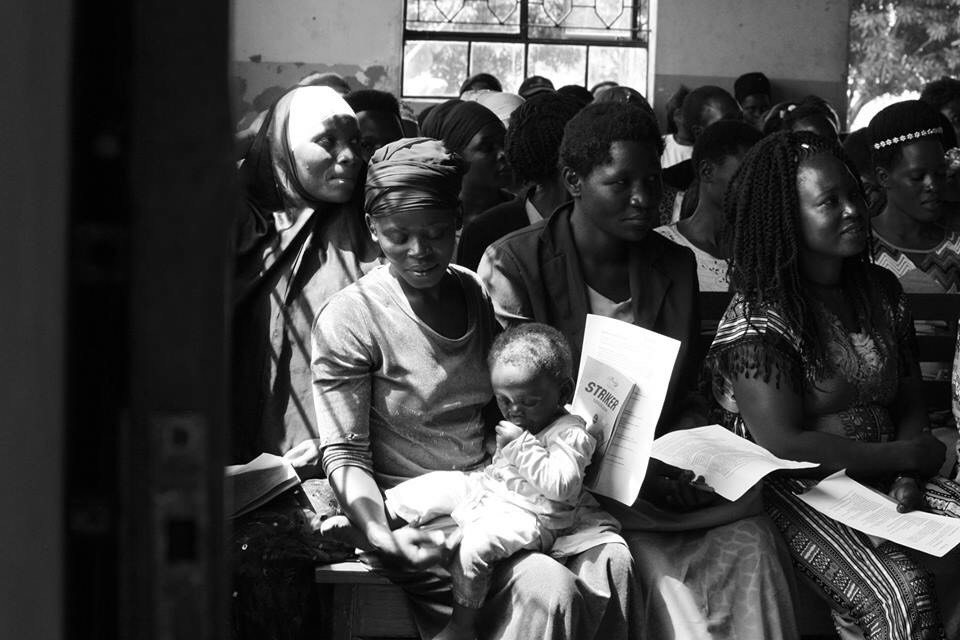

CHPs help deliver basic maternal and child care “door-to-door,” promote healthy living practices in their community, and treat four priorities: malaria, diarrhea, pneumonia, and malnutrition. Simultaneously, CHPs earn income by selling Living Goods health products—from treatment medication at low prices to high-nutrition porridge mixes. The women in Buyengo—over 120 people had shown up, more than expected—were CHP candidates. They had just heard a pitch about Living Goods and the responsibilities and benefits of being a CHP, and were staying for the interview screening to follow.

Their presence, an important part in a multi-step expansion process currently underway, is a testament to the draw and future potential of the Living Goods idea. Since the organization began in 2007, it has grown and successfully trained over 2,000 of its own CHPs. In our first few weeks in Uganda, we were able to see that the model does, in many ways, work. We saw women checking on sick children in neighboring households, administering malaria tests and treatments, and, in turn, earning income that has paid for their own children’s school fees. The CHPs we spoke with said they felt that sickness had decreased in their communities, that they had gained respect amongst their neighbors.

The challenge now faced by the non-profit is bringing their model to scale. Living Goods aims to have 10,000 CHPs within their network by 2021, which means that they must (1) retain and incentivize high performance from existing CHPs, and (2) rapidly recruit quality CHPs in new regions. Living Goods’ future success and impact depends on a careful balance of quality, quantity, and time.

Simon, Nadira, and I are working with the direct operations team and a regional, soon-to-be “super” branch in Mafubira to see how various current processes—such as CHP workload and goal management—can be optimized for long-term sustainability, and how the current expansion drive can be more efficient. To do that, we’re following various parts of the expansion process and interviewing current CHPs to find out how the model can work better for them.

In Buyengo, where the unexpectedly high number of women interested in the program means that interviews take until nightfall, we try to integrate fully with the expansion team. For those candidates who can understand our American accents, we conduct difficult interviews ourselves that throw the expansion team’s challenges into focus: what motivates a candidate? Are they truly committed to Living Goods, or just temporarily excited? How should we consider candidates with weaker skills but stronger ties to their community, and vice versa?

By the time candidates have been interviewed, it’s a result of weeks of previous groundwork: mapping, in which village data is collected for potential CHP recruitment, and mobilization, where relations with local leaders are developed so that they can refer qualified women who might make strong CHPs. The women in Buyengo have stayed through the presentation, an exam, the interview— all of which made for a long day. For the expansion team though, and for Living Goods at large, the key question is whether these women will stay in the long run through three weeks of training, through assessments, and through several years to impact the health of communities as high-performing CHPs. Over the coming weeks, we hope to find ways to make sure that they do.