The Impact of Large-Scale Forced Displacement on Rohingya Refugees and Host Communities in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh

Researchers: Sarah Baird (George Washington University), Austin Davis (American University), Paula López-Peña (Yale MacMillan Center), A. Mushfiq Mobarak (Yale University), Jennifer Muz (George Washington University), Nethra Palaniswamy (World Bank) and Tara Vishwanath (World Bank).

Researchers: Sarah Baird (George Washington University), Austin Davis (American University), Paula López-Peña (Yale MacMillan Center), A. Mushfiq Mobarak (Yale University), Jennifer Muz (George Washington University), Nethra Palaniswamy (World Bank) and Tara Vishwanath (World Bank).

Contact: A. Mushfiq Mobarak, Professor of Economics, Yale University, ahmed.mobarak@yale.edu

Despite the scale and persistence of forced displacement, little data and evidence exists to inform long-term policy responses. The arrival of hundreds of thousands of refugees in southern Bangladesh beginning in August 2017 poses a significant policy question: how to integrate refugees into the host economy while simultaneously maintaining or improving the wellbeing of nationals. Researchers are working with IPA to collect detailed social, economic, and health data from previously arrived refugees, recently arrived refugees, and Bangladesh nationals in southern Bangladesh to explain the impact of the recent large refugee flow on the host economy.

Policy issue

By the end of 2018, a record 70.8 million people were forcibly displaced as a result of conflict, persecution, or violence. Developing countries, and the least developed countries in particular, hold a disproportionately large responsibility for hosting refugees, despite having the least resources to respond to the needs of refugees and the communities that host them. Some of the poorest countries in the world host about 33 percent of the world’s refugee population, while only being home to little over 10 percent of the world’s general population.[1]

Policymakers in host countries often perceive a conflict between the needs of refugees and the wellbeing of country nationals. Refugees are thought to compete with nationals for scarce opportunities and resources such as schooling, jobs, housing, and public services. Consequently, refugees face significant barriers to social and economic integration in their host countries, are often forced to rely on government or NGO aid to meet their basic needs and struggle financially. Though there are more refugees now than at any time since World War II, little data or evidence exists to inform long-term policy responses to refugee crises and explain the impact of refugee flows on host economies. The aim of this research is to better understand the ways in which the challenges faced by Rohingya refugees while they were living in Myanmar are likely to affect their ability - and the ability of future generations of Rohingya - to attain a better living standard in their host communities, with a view to informing policy and programming.

Evaluation Context

The Rohingya have faced decades of systematic discrimination, persecution, statelessness, and violence in Myanmar, which has forcibly displaced Rohingya refugees into Bangladesh after waves of violence in between 1978 to 2017. As of July 2019, over 742,000 refugees - disproportionately women and children - fled to Bangladesh after a breakout of violence in August 2017.

Most newly arrived refugees have settled in southern Bangladesh, near the border with Myanmar. According to the UNHCR, approximately 671,000 refugees arrived in southern Bangladesh’s Cox’s Bazar district since August 2017. This district had already some 213,000 Rohingya who had fled to Bangladesh in previous years. Refugees now constitute more than a third of the total population of Cox’s Bazar.[2]

Details of the Intervention

This is not a randomized controlled trial.

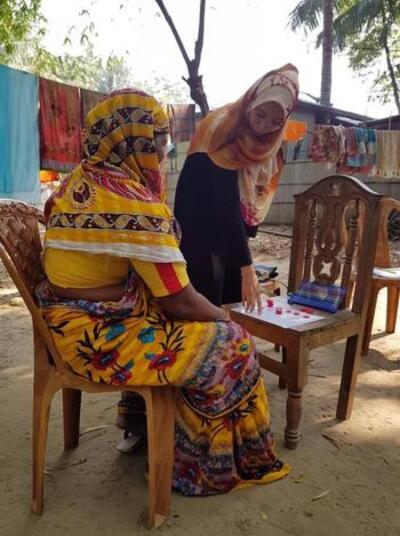

Researchers are collecting detailed social, economic, and health data from previously arrived refugees, recently arrived refugees (post-August 2017), and Bangladesh nationals through a series of surveys of 5,020 households in Cox’s Bazar District. The research team will conduct three rounds of the survey with one to three years between each round. The survey will ask Cox’s Bazar residents a series of questions on demographics, work, schooling, health, assets, consumption, aid, social and family networks, physical and mental health, dispute resolution, and political attitudes. The survey will provide a description of how local economies change in response to an influx of refugees, important data for future research, and guidance for policymakers in Bangladesh and others who respond to refugee crises.

The quantitative data collection is complemented with qualitative interviews with adolescents and their caregivers.

Results and Policy Lessons

Preliminary results; further results are forthcoming.

Rohingya refugees, especially women, in Cox’s Bazar have low educational attainment in absolute and relative terms. Only 30 percent of male residents in refugee camps have at least completed primary school, and that figure is around 10 percent among female residents. Refugees’ educational attainment is much lower than the average in Myanmar, where about 66 percent of men and 55 percent of women have completed primary.[3] Refugee attainment is also below that of Bangladeshi residents in Cox’s Bazar; about half of both men and women in the host community have completed primary.

Comparing the periods before and after displacement, employment rates increased modestly in the host community. About 88 percent of prime-age host-community men reported being employed at some point in the year prior to the arrival of refugees; that figure rises to 93 percent for the period after refugee arrival. Prime-age host-community women are much less likely to work overall, but also see modest gains in employment rates from 24 to 29 percent.

While refugees were similarly productive to hosts prior to displacement, post-displacement earnings are much lower. Controlling for demographic differences, earnings were nearly identical in the host and refugee communities prior to displacement. After displacement, the ability of refugees to earn a livelihood is significantly constrained in Cox’s Bazar with refugees earning much less than hosts.

A high percentage - 44 percent of those who were in Myanmar in 2017 and 38 percent of all other Rohingya refugees - report having had a family member or a friend killed in their lifetime. Responses to open-ended questions show that many respondents experienced or witnessed the death of many family members. A quarter of all Rohingya households living in camps were female-headed, compared to 18% of host communities and 12.5% of Bangladeshi households overall, suggesting a relatively high rate of loss of male family members.

Although household size is similar (5.2 in both communities), Rohingya refugees in camps had on average 1.2 dependents relative to working-age household members, compared to 0.8 in host-community households, reflecting the greater economic vulnerability of recent refugees. Qualitative findings suggest that this is leading to a disruption of gender norms around the acceptability of work in some households, with more adolescent girls and women going outside the home for income-generating purposes.

Despite reports that their assets were often confiscated, stolen, or destroyed, Rohingya living in Myanmar in July 2017 owned more assets than Rohingya living elsewhere at that time, suggesting it is difficult for households to accumulate wealth after they are displaced. Displacement itself represents a significant loss of wealth and productive capacity: assets that were widely owned prior to displacement, especially livestock and residences, are almost all left behind.

[1] UNHCR (2019) “Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2018”, June; https://www.unhcr.org/5d08d7ee7.pdf

[2] UNDP (2018) “Impacts of the Rohingya Refugee Influx on Host Communities”, November https://www.undp.org/content/dam/bangladesh/docs/Publications/Pub-2019/Impacts%20of%20the%20Rohingya%20Refigee%20Influx%20on%20Host%20Communities.pdf

[3] Calculated from the 2017 Myanmar Labor Force Participation Survey.