Yale nursing’s international approach brings care and education to Africa

Ann Kurth, dean of Yale’s School of Nursing, wants you to understand the vital importance of nurses and midwives to healthcare systems around the globe, including in sub-Saharan Africa and other developing regions.

“Nurses run hospitals. They run entire health systems, yet despite their immense contributions, they don’t always get recognized for their capabilities,” said Kurth, the Linda Koch Lorimer Professor of Nursing and an expert in global health. “They are often overlooked as candidates for leadership opportunities that would enable them to contribute in an even greater way. This is simply wasteful.”

Nurses touch nearly every aspect of health care in the United States and around the globe, notes Kurth. The World Health Organization has noted that 80% of all healthcare worldwide is delivered by nurses and midwives. In the U.S., the National Academy of Medicine has pointed out that improving the health system will rely on allowing nurses to practice to the full scope of their training.

“Every day, nursing has a ripple effect in the world, given how critical and central the role is to the health of individuals, families, communities, and entire nations,” Kurth added. “In a community, there are no sustainable pathways to economic prosperity without health, and there’s no health without nurses and midwives.”

Under Kurth’s leadership, the faculty of Yale’s School of Nursing produces advanced practice registered nurses (nurse practitioners, nurse midwives) who deliver cost-effective, patient-centered primary and specialty care. Through its Ph.D. and clinical doctorate programs Yale Nursing also produces the next generation of scientists and educators.

According to Kurth, the school’s mission rests on three legs: furthering education, conducting scientific research and scholarship, and performing service at the local, national, and international levels. Kurth’s work in sub-Saharan Africa embodies much of this three-legged approach, as well as the all-encompassing nature of nursing’s essential role in delivering health care.

Education, science, service

Kurth and many others from the school engage in numerous partnerships and projects to strengthen health systems, including in sub-Saharan Africa, a region that accounts for 12% of the world’s population, 23%-26% of its disease burden, but less than 1% of world health expenditures.

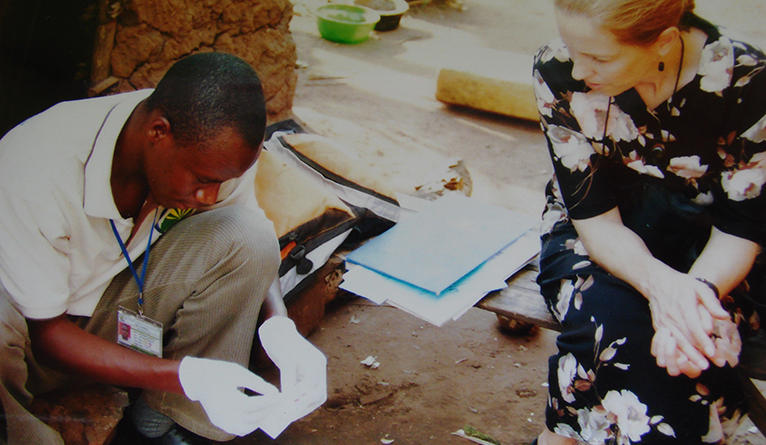

She has worked with Kenya’s Ministry of Health to evaluate a national needle syringe exchange program and improve hepatitis C treatment in the country. She has led research on HIV prevention, including a recently completed study that combined interventions, such as voluntary medical circumcision for males, pre-exposure prevention for high-risk females, and cash transfers for HIV-negative youth at high risk of becoming infected.

Kurth has partnered with Kenyatta National Hospital, the University of Nairobi, and Impact Research and Development Organization on a National Institutes of Health-funded implementation science study focused on increasing access to HIV testing, prevention and treatment for high-risk young women.

“Our current research in Kenya is to understand how to motivate people to self-test for HIV,” she said. “We’re exploring ways to get people to check their status and to stay engaged with treatment, enabling a healthy life for them and limiting the spread of the infection.”

Yale School of Nursing faculty and students also have worked in Africa — in areas from HIV to palliative care, oncology, and reproductive health — work that demonstrates the three legs of the school’s mission, Kurth said.

Rose Nanyonga Clarke, who earned her nursing Ph.D. from Yale in 2015, shows that the first leg of the school’s mission — education — is having a positive impact in Africa.

After graduation, Nanyonga returned to her native Uganda where she is the vice chancellor of the International Health Sciences University, a new private university affiliated with a leading hospital that boasts a newborn intensive care unit and an extensive ambulance system connected to 22 clinics.

“Rose successfully manages and leads what I would argue is one of the best-run hospitals in East Africa,” said Kurth.

Nanyonga credits much of her success to her Yale education and experience, in particular the specific leadership insights she learned from the school’s faculty.

“Our faculty pushed and challenged her, and I could say the same thing about my experience — we share a bond in the story of what Yale can do to help shape and to support students and their career trajectories,” said Kurth, who graduated from Yale School of Nursing in 1990. “To see how Rose has used her Yale education to have such a powerful impact on the health of her community and continent is phenomenal. It serves as the perfect example for every student at our school.”

Building a robust and sustainable corps of highly educated nurses like Nanyonga is critical to improving healthcare in Africa, Kurth said. Nurses managing complex care have enabled people to live longer throughout the continent. In South Africa alone, studies have shown that nurses delivering HIV care have saved hundreds of thousands of lives, she said.

“In aggregate, thanks in part to advances made by nursing, the world is better off than it has ever been. Nurses work across a continuum of care that spans birth to death, and they help people live healthy lives in between,” said Kurth. “We’ve had huge advances in aggregate human health, gaining five and a half years in average life expectancy around the world, and nine and a half years in sub-Saharan Africa. That’s very powerful.”

‘Better health for all people’

Kurth, an epidemiologist and certified nurse-midwife, comes from a family of health professionals. Her father was a physician and her mother was a nurse. During Kurth’s childhood, her family performed volunteer work on a Navajo reservation domestically, and abroad in Puerto Rico, Guatemala, and Nicaragua.

“I grew up seeing the numerous ways that people live, in a variety of contexts and with different resources, around the world,” Kurth said. “Those lessons stuck with me and helped me fully realize and appreciate the critically important role healthcare providers play in their communities everywhere.”

Over her career, Kurth has learned to appreciate the world’s interdependence — how a problem or solution in one part of the world can affect other parts of the world. She said nursing is a microcosm of that trend — the scholarly and clinical work nurses perform in one country can reverberate past national borders and across oceans. Ensuring that the work reaches populations is the next opportunity, in Africa and elsewhere, she adds.

“It’s not sufficient anymore to simply secure a grant, conduct a four-year randomized trial, produce a few papers and feel the job is finished,” she said. “If we’re going to have a meaningful impact on health conditions today we must also take that work, the evidence discovered, and put it into practice at scale.”

Kurth believes universities are not simply centers for generating knowledge, but are responsible for putting knowledge into practice by producing and deploying leaders who can make a difference across all health care.

She also believes that nurses have a professional responsibility to advocate for their patients, which encourages taking a social-justice approach to delivering care.

“Our school’s official mission statement is ‘Better health for all people,’ so embedded in that is the idea of equity,” said Kurth. “Everyone deserves a healthy life, and access to equitable, quality healthcare. That frames what we do every day.”