Freedom: Page 1

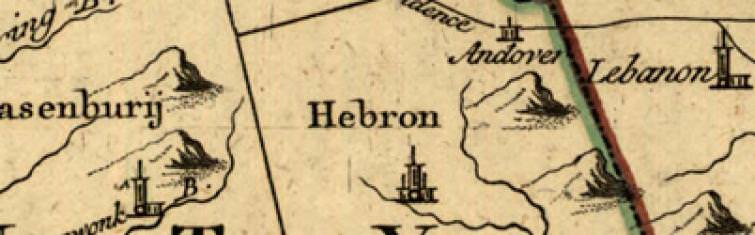

The story of Cesar and Lowis Peters and their children illustrates, in all its complexity, late eighteenth-century enslavement in Connecticut. This trusted and hardworking Hebron couple, for many years the property of an Anglican minister named Samuel Peters, continued to work the Hebron farm of their Tory master after he fled to England during the American Revolution.

Cesar and Lowis, though enslaved, independently worked the Peters’ property from 1776 until 1787, when a relative of the minister arrived to claim the black family and sell them. Community regard for the couple was so high, however, that the townspeople of Hebron staged an elaborate subterfuge and spirited them away from their captors.

The black couple illuminates both the industry of Connecticut’s enslaved, and their profound vulnerability. Lowis and Cesar had a town rally around them, but many of the enslaved and newly freed did not. Venture Smith, an African-born prince who was a slave in the colonies and Connecticut for nearly 30 years, managed to buy his freedom in the 1760s and wrote a bitter memoir about his life as a slave and free man. Things that would have been judged a crime in Africa, he wrote, were good enough for “the black dog.”

Well before the war for emancipation, Connecticut began drawing to a close its on-site relationship with slavery. Black men and women were taking their place in a free society, and the state’s policy of gradual manumission, instituted in 1784, was moving toward its desired goal.

And yet, as always, the story is more complex than we might like to assume. To understand America’s tug-o-war over enslavement, you need only look at Connecticut during the last 25 years of the eighteenth century. A thriving colony became a thriving state and even as its economic dependence on slavery deepened—fortunes made in the Triangle Trade were underwriting every kind of new enterprise—the numbers of enslaved began to decline.

Shortly before the Revolution, Samuel Johnson asked: “How is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of negroes?” The great English writer had a point and it was not lost on Americans about to wage war for national and economic independence. The incongruity of “liberty and justice for all” and a population held in chattel bondage was, at least to some, inescapable.

Related links:

Read Venture Smith’s autobiography

See “Documents and Activities” for archival materials about Cesar and Lowis

Watch a short film about Cesar and Lowis