Independence and the Representational Crises

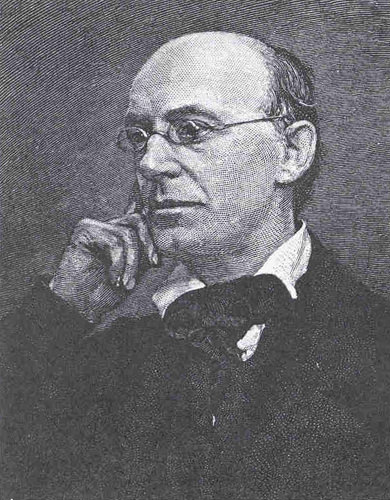

William Lloyd Garrison, an engraving from a daguerreotype made in Dublin in 1846.

But even this last example illustrates a partial truth in Webb and Chapman’s apprehensions about the pernicious effects of Douglass’s popularity. As adamantly as Douglass defended Garrison, the very fact that it was he who was doing the defending highlighted the changing nature of Douglass’s participation in abolition. And so even if we do discount Webb’s allegations, we must recognize that the British environment did indeed put pressure on Douglass to assert his independence in the sense that it encouraged him to question and reevaluate his involvement in antislavery. This relationship between independence and self-examination was critical for Douglass. From the first pages of his Narrative, in which he lamented his unrecorded slave past, Douglass associated slavery with a lack of personal information. Thus, the transition from chattel to man was linked in his mind with the privilege of self-exploration and self-expression. It is for this reason that Douglass was so sensitive to condescension and paternalism in Britain; for someone engaged in such intense self-scrutiny, the suggestion that he needed “adult” supervision was especially troublesome, and challenged the progress he had made since his days on Auld’s plantation.

But even this last example illustrates a partial truth in Webb and Chapman’s apprehensions about the pernicious effects of Douglass’s popularity. As adamantly as Douglass defended Garrison, the very fact that it was he who was doing the defending highlighted the changing nature of Douglass’s participation in abolition. And so even if we do discount Webb’s allegations, we must recognize that the British environment did indeed put pressure on Douglass to assert his independence in the sense that it encouraged him to question and reevaluate his involvement in antislavery. This relationship between independence and self-examination was critical for Douglass. From the first pages of his Narrative, in which he lamented his unrecorded slave past, Douglass associated slavery with a lack of personal information. Thus, the transition from chattel to man was linked in his mind with the privilege of self-exploration and self-expression. It is for this reason that Douglass was so sensitive to condescension and paternalism in Britain; for someone engaged in such intense self-scrutiny, the suggestion that he needed “adult” supervision was especially troublesome, and challenged the progress he had made since his days on Auld’s plantation.

Douglass’s examination of his identity while in Britain was shaped partly by the nature and expectations of his audience, and partly by his own instincts for self-expression, development and growth. Fundamentally, before this new audience Douglass had to develop a role that incorporated both his antislavery duties and the shifting outlines of his self-perception. Though Douglass had more freedom to make these decisions than he had when touring in the United States under the direction of the AASS, he by no means had a tabula rasa upon which to sketch his ideal persona. His visit was part of an ongoing conversation among abolitionists about the most effective relationship between the individual agent and the cause espoused. In 1844, Henry Wright wrote to Wendell Phillips of the ideal antislavery lecturer in Britain: “It needs a White abolitionist to do the work there—a Colored one would not do half as well. The sympathy of Britain would flow out toward him personally, as a proscribed & deeply injured individual—rather than towards the Anti-Slavery cause. Sympathy with an individual…is of little use in our great struggle for human freedom.”[95] If Phillips had agreed with Wright then, he must have changed his mind by the time of Douglass’s proposed visit. Encouraging Douglass to go to Britain as the representative of both abolitionists and “his brethren in bonds,” Phillips advised him, “Be yourself, and you will succeed.”[96] His advice can be viewed as a response to Wright’s earlier comment; whereas Wright suggested that to be successful overseas, the antislavery agent must repress his own individuality, Phillips proposed just the opposite: that Douglass’s success would depend on the extent to which he was true to his own character and experiences, and was able to communicate them to his audience.

Though Douglass accepted the relationship between success and self-realization established by Phillips, ironically, he also followed the logic of Wright’s suggestion, struggling to find the proper place for his own experiences in his antislavery personality. That struggle reveals the complex and paradoxical nature of Douglass’s representative identity. Indeed, Douglass was perceived by his British audiences as something like a walking paradox, “a living contradiction…to that base opinion…that the blacks are an inferior race.”[97] Similarly, Douglass claimed that as an “intellectual coloured man,” he represented “a contradiction” to the racial theories of slave owners as well.[98] (SOURCE) Essentially, Douglass’s role was paradoxical; he was meant to serve as an exceptional representative, challenging conventional stereotypes and breaking boundaries of prejudice by embodying their contradiction. As one enthusiastic supporter wrote from Wrexham, Wales, Douglass “is a living example of the capabilities of the slave, and though we do not expect all to be equally gifted, he proves that they are not what they have been mis-represented, mere chattels…”[99] Douglass represented the potential of American slaves, but a potential necessarily distanced from their degraded condition that provoked audience sympathy.

Despite this distance, Douglass initially based his representational identity upon his shared slave experiences. As he said before a Dublin audience “I am the representative of three million of bleeding slaves. I have felt the lash myself; my back is scarred with it; I know what they suffer.”[100] (SOURCE) This attitude reflected the pressure applied by white abolitionists toward their black counterparts to define their antislavery personas strictly experientially. For all of the tolerance and equalitarianism of Garrison’s Boston Clique, they placed definite restrictions on blacks’ involvement in antislavery. Generally, Garrisonians assumed that blacks should limit their presentations to a narration of wrongs, and because of their presumed educational deficiencies, should resist undertaking a discussion of policy. “Give us the facts,” Collins instructed Douglass during their western tour, “We will take care of the philosophy.”[101]

As John Blassingame has suggested, it is quite possible that in his autobiographies Douglass exaggerated the tendency of white abolitionists to restrict his lectures to a discussion of “the plantation.” The evidence from accounts of his speeches shows that as early as 1841 Douglass had expanded the scope of his presentations to include material beyond a narration of his own experience.[102] But even if Douglass did have more freedom than he admitted, the fact that he imagined this conspiracy in so many variations demonstrates the extent to which he felt restrained by the public role imposed upon him.

These pressures were further amplified by the demands of British audiences. Distanced from the cruel realities of slavery by the Atlantic, many audience members had never actually seen a slave before, and they expected Douglass to satisfy their curiosities, and often, to provide them with lurid accounts of brutality and violence. Thus, unlike his white counterparts, audience members rarely charged Douglass with sensationalism or extremism.[103] Like the exotic exhibits displayed in the Crystal Palace a few years later, Douglass’s very presence, as well as his rhetorical talents, was meant to animate the imaginations of his audience, leading them past the image of the talented orator to the slave plantation itself.

At first Douglass satisfied these expectations without reserve, holding up before an Irish audience a whip still clotted with blood, and reminding them of his own scarred back; telling the horrible story, in graphic detail, of a slave whose ear was nailed to a post, and who in a desperate attempt to escape, tore herself away, leaving only the bloody ear behind (SOURCE); or recounting his early memory of seeing his own cousin Henny stripped naked and savagely beaten by his master.[104] (SOURCE) But as his celebrity increased, though he was still willing to describe the general brutality of slavery, and vividly narrated the experiences of other slaves, Douglass began to resist including examples from his own life. When he did offer such examples, he often apologized for them, justifying the material as absolutely necessary in order to “let the slave holders of America know that the curtain which conceals their crimes is being lifted abroad.”[105] (SOURCE) Alternatively, Douglass avoided absolute self-disclosure by constructing imaginary or hypothetical scenarios of his experiences. In one striking example, Douglass led the audience in a frightening reverie in which he was once again a slave, and was sold down South by his old Master Auld in order to raise the extra money for a contribution to the visiting Free Church delegation.[106] (SOURCE) By May of 1846, Douglass could tell a London audience that unlike his speaking requirements in the United States—”to go into a detail of the cruelty practiced on the slaves”—before this audience he thought it more effective to “point out the means by which slavery is upheld.”[107] (SOURCE)

There are several reasons for this shift in emphasis. In general, while overseas, American abolitionists concentrated on the ways in which slavery was supported by fellowship from abroad, as demonstrated by their ferocious battles with the Free Church and the Evangelical Alliance. Abolitionists were convinced that slavery could be eradicated if slaveholders were denied the oxygen of international support. As Douglass said, “I want the slave holder surrounded, as by a wall of anti-slavery fire, so that he may see the condemnation of himself and his system glaring down in letters of light. I want him to feel that he has no sympathy in England, Scotland, or Ireland.”[108] (SOURCE) Additionally, Douglass admitted that his own sufferings with slavery were not representative; he was lucky to enjoy a relatively privileged and carefree life for a slave. Maryland slavery was considerably more “enlightened” than the plantations further South and, from an early age, Douglass enjoyed the favor, and even the indulgence, of his white masters and mistresses.[109] In the United States, under the direction of Garrison, Douglass was required to submit to the demands of abolitionist propaganda and present his own life as a sort of “extended historical narrative,” repressing as much as possible those idiosyncratic elements of his personal history that did not reveal the general cruelties of slavery. Douglass broke free from these restraints to some extent in his Narrative, revealing specific place names and details of his life to verify his authenticity. But even in the Narrative, Douglass often sacrificed his individuality to the more general moral duty of denouncing slavery.[110] In Britain, Douglass took an even bolder step toward asserting his right to travel beyond the “simple narrative.” In this sense, the public persona Douglass adopted in Britain should be considered as an oratorical variation of what Robert Stepto has identified as Douglass’s liberating “acts of literacy”: his Narrative in 1845, The North Star in 1847, and his novella “The Heroic Slave” in 1853.[111] Paradoxically, in Britain Douglass expressed his individuality not by asserting his self, but by extracting it—liberating it—from his antislavery routine. Thus, Douglass told one English audience, with the unmistakable air of one who owns his own story, “I could give you accounts of myself, but really I am almost tired of speaking of my own individual case to assemblies like this. I have suffered much, but nothing in comparison to thousands of others.”[112] (SOURCE)

Since Douglass often provided graphic accounts of slavery nonetheless, these qualifications were probably more for his own benefit than for his audience’s, not so much antislavery material as his transatlantic efforts at redefinition. Douglass resisted offering examples from his own slave life because, surrounded by the luxury of British society, and enjoying a newly confirmed sense of gentility, that slave past became increasingly more difficult to access. In one letter to Garrison, Douglass described the memory of the degradation of slavery as “more like a dream than a horrible reality.” Ironically, this letter was in response to an accusation by an American pro-slavery apologist, who apparently knew Douglass when he was Frederick Baily. He claimed that Douglass could not have written the Narrative, for Baily was “an unlearned and rather an ordinary Negro.” This is a variation of the charge that motivated the composition of the Narrative and ultimately sent Douglass overseas; that there was an unresolvable inequality of identities between the individual who experienced slavery and the individual who later narrated that experience. But though the trip abroad was brought about by Douglass’s need to affirm in writing his slave past, it threatened to distance him from that past, and from that class of people whom he was called to represent. Beyond the sarcasm, Douglass was speaking seriously when he responded: “I can easily understand that you sincerely doubt if I wrote the narrative….Frederick Douglass, the freeman, is a very different person from Frederick Baily…the slave. I feel myself almost a new man—freedom has given me a new life.”[113] (SOURCE)

Footnotes

[95] Cited in Friedman, Gregarious Saints, 184.

[96] Cited in Foner, Frederick Douglass, 62.

[97] Cited in Blassingame, Frederick Douglass Papers, “Introduction,” lv.

[98] Blassingame, Frederick Douglass Papers, II:5 (February 2, 1847) (SOURCE).

[99] Cited in Fulkerson, “Exile as Emergence,” 72.

[100] Blassingame, Frederick Douglass Papers, I:36 (October 1, 1845) (SOURCE).

[101] Douglass, My Bondage, My Freedom, 281; Friedman, Gregarious Saints, 188. These beliefs resurfaced in the resistance to Douglass’s role as an editor, with the establishment of The North Star in 1847.

[102] Blassingame, Frederick Douglass Papers, “Introduction,” xlviii-lii.

[103] Blackett, Building an Antislavery Wall, 95; Pease and Pease, They who would be Free, 50; Fulkerson, “Exile as Emergence,” 74.

[104] Blassingame, Frederick Douglass Papers, I:35 (October 1, 1845) (SOURCE), I:42 (October 14, 1845) (SOURCE), I:86 (November 10, 1845) (SOURCE), I:401 (SOURCE).

[105] Blassingame, Frederick Douglass Papers, I:274 [May 22, 1846] (SOURCE).

[106] ibid, I:180 (March 10, 1846). See also, I:193. (SOURCE)

[107] ibid, I:255 (May 18, 1846) (SOURCE).

[108] ibid, I:295 (May 22, 1846) (SOURCE).

[109] Quarles, Frederick Douglass, 5; Moses, “Writing Freely?,” 74; Blassingame, Frederick Douglass Papers, I:400 [September 11, 1846] (SOURCE). The special treatment Douglass received was probably due to the fact that his father was white, and most likely his master, Thomas Auld. See McFeely, Frederick Douglass, 13.

[110] Walker, Moral Choices, 224; Moses, “Writing Freely?,” 69-73.

[111] Stepto, “Storytelling,” 358.

[112] Blassingame, Frederick Douglass Papers, I:375 (September 1, 1846) (SOURCE).

[113] Foner, Life and Writings, I:133 (January 27, 1846) (SOURCE).

[114] McFeely, Frederick Douglass, 136.

[115] Foner, Life and Writings, 126 (January 1, 1846) (SOURCE); Blassingame, Frederick Douglass Papers, I:222 (April 17, 1846) (SOURCE).

[116] Foner, Life and Writings, I:169 (May 23, 1846) (SOURCE). Blassingame, Frederick Douglass Papers, I:269-299. (SOURCE)

[117] Frederick Douglass to “My Own Dear Sister Harriet,” July 1846 [photostat], Frederick Douglass Papers, WVU.

[118] Blassingame, Frederick Douglass Papers, I:416 (September 14, 1846) (SOURCE); Foner, Life and Writings, I:126 (January 1, 1846) (SOURCE); I:181 (July 23, 1846) (SOURCE). See also Russ Castronovo, “As to Nation, I Belong to None: Ambivalence, Diaspora, and Frederick Douglass,” American Transcendental Quarterly 9:3 (September 1995) for a discussion of Douglass’s perception of exile and nationality.

[119] Foner, Life and Writings, I:149 (April 6, 1846) (SOURCE). See also Blassingame, Frederick Douglass Papers, I:125 (January 2, 1846) (SOURCE).

[120] Blassingame, Frederick Douglass Papers, II:60 (May 11, 1847) (SOURCE).

[121] Frederick Douglass to “My Dear Harriet [Baily],” August 18, 1846 [photostat], Frederick Douglass Papers, WVU.

[122]See letters from Isabel Jennings, Mary Ireland, Frances Armstrong, Mary Estlin, and Jane Carr in Taylor, Transatlantic Understanding, 243-300. See also, Freeman’s Journal (Dublin), September 10, 1845.

[123] Taylor, Transatlantic Understanding, 305. Webb repeated almost the same fear about Douglass to Chapman, cited in Blackett, Building an Antislavery Wall, 112.

[124] Henry Louis Gates Jr., “A Dangerous Literacy: The Legacy of Frederick Douglass.” The New York Times Book Review, May 28, 1995, p.16; Terry Pickett, “The Friendship of Frederick Douglass with the German, Ottilie Assing.” The Georgia Historical Quarterly 73:1 (Spring 1989), 97. For a very different image of Anna Douglass, see the essay by her daughter, Rosetta Douglass Sprague, “Anna Murray-Douglass—My Mother as I Recall Her.” Journal of Negro History 8 (January 1923). Rosetta presents her mother as an intelligent, if uneducated, domestic executive, whose loyalty and hard work were a silent and essential element of Douglass’s successful career.

[125] While Douglass was speaking in Belfast, a rumor circulated that he was seen walking out of a Manchester brothel; Douglass was furious and charged the Free Church minister he suspected was behind the rumor with libel. Douglass eventually extracted an apology from a Rev. Thomas Smyth, but the tactic of preying upon Douglass’s sexuality would be a constant and effective weapon in the arsenal of his antagonists. Many of these attacks focused on Douglass’s controversial relationship with Julia Griffiths, a close friend whom Douglass met in Britain. Griffiths came to Rochester in 1849 in order to help Douglass edit and handle the finances of his antislavery newspaper, The North Star. She stayed for a while in his home, and her presence caused something of a scandal in the abolitionist community. Many assumed that Griffiths’ relationship with Douglass was romantic as well as professional. Douglass denied this and was deeply saddened by the charges. Blackett, Building an Antislavery Wall, 85. See letter from Thomas Smyth to ‘Gentlemen’ (July 28, 1846) apologizing for the slander, Frederick Douglass Papers, General Correspondence, Library of Congress; Taylor, Transatlantic Understanding, 273. Foner, Frederick Douglass, 87-90; McFeely, Frederick Douglass, 163-170.

[126]Recent feminist studies of Douglass’s Narrative have demonstrated the extent to which Douglass uses the feminine as a “synecdoche” for slavery. In her essay “The Punishment of Esther: Frederick Douglass and the Construction of the Feminine,” in Sundquist (ed.) Frederick Douglass: New Literary and Historical Essays, Jenny Franchot suggests that Douglass feminizes slavery so that he can rhetorically “master the subject.” Another possibility is that slavery was feminized in Douglass’s mind by its connection to the dark, illiterate Anna, and through the vague but powerful image of his (literate) slave mother.

[127] Blassingame, Frederick Douglass Papers, I:270 (May 22, 1846) (SOURCE). Blassingame locates these self-deprecatory introductions in the conventions of Victorian rhetoric, but I maintain that they had a special meaning for Douglass as a rhetorical reenactment of his progression from bondage to freedom.

[128] Frederick Douglass to “My own Dear sister Harriet [Baily],” May 16, 1846 [photostat], Frederick Douglass Papers, WVU.

[129] Blassingame, Frederick Douglass Papers, I:134 (January 15, 1846) (SOURCE). See also Blassingame, Frederick Douglass Papers, II:23 (March 30, 1847). (SOURCE)

[130] McFeely, Frederick Douglass, 137, 143; Blassingame, Frederick Douglass Papers, I:482n. See also Bill of Sale, November 30, 1846, and deed of manumission, December 12, 1846, in Frederick Douglass Collection, Reel One, Library of Congress.

[131] Blassingame, Frederick Douglass Papers, II:43 (March 30, 1847) (SOURCE). Douglass was not the only escaped slave to grapple with this issue. William Wells Brown and James Pennington also raised enough money during their travels in Britain to buy their freedom. Pease and Pease, They who would be Free, 62.

[132] Cited in Quarles, Frederick Douglass, 52. See Aileen Kraditor, Means and Ends in American Abolitionism (New York: Vintage Books, 1967), 220-221 for more examples of opposition.

[133] Kraditor, Means and Ends, 222. See also Garrison’s letter to Elizabeth Pease, April 1, 1847 (SOURCE), in Walter Merrill (ed.), The Letters of William Lloyd Garrison, Volume III: No Union With Slaveholders 1841-1849 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1973), 476.

[134] See for instance the reaction of M. Welsh and the Edinburgh Ladies Antislavery Association in Taylor, Transatlantic Understanding, 300, or that of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society in Kraditor, Means and Ends, 220.

[135] Henry Wright to Frederick Douglass, December 12, 1846 [photostat], Frederick Douglass Papers, WVU. Wright seems here to contradict his statement to Phillips in 1844, rejecting the importance of sympathy for an antislavery agent.

[136] Blassingame, Frederick Douglass Papers, II:28 (March 30, 1847) (SOURCE).

[137] ibid, I:188 (March 19, 1846) (SOURCE); I:346, 357, 374.

[138] Foner, Life and Writings, 1:200 (December 22, 1846) (SOURCE).

[139] Foner, Life and Writings, I:206 (December 22, 1846) (SOURCE).

[140] Friedman, Gregarious Saints, 190.

[141] Walker, Moral Choices, 245. See McFeely, Frederick Douglass, 147 for a letter in which Quincy calls Douglass an “unconscionable nigger.”

[142] Frederick Douglass to my Dear Friend [Amy Post], April 28, 1846 [photostat], Frederick Douglass Papers, WVU. See also My Bondage and My Freedom, 312.

[143] Frederick Douglass to Francis Jackson, January 29, 1846, Anti-slavery Collection, BPL (SOURCE).

[144] Cork Examiner, October 15 1845. (SOURCE) Not all abolitionists considered Douglass’s white blood a blessing. The daughter of Thomas Clarkson, the British abolitionist patriarch, upon first meeting Douglass, wrote: “What an extraordinary man Douglass must be! I wish he were full blood black for I fear your pro-slavery people will attribute his pre-eminent abilities to the white blood that is in his veins.” Taylor, Transatlantic Understanding, 275.

[145] Cited in Quarles, Frederick Douglass, 35.

[146] Walker, Moral Choices, 246, 254-257; Martin, Mind of Frederick Douglass, 3-4. Douglass grapples with his paternity, and thus, with his racial identity, in the fascinating “Letter to My Old Master, Thomas Auld.” (SOURCE) The letter was published in the September 1848 edition of The Liberator, and was written to mark the tenth anniversary of Douglass’s escape from slavery. But in the original edition of My Bondage and My Freedom, published in 1855, a footnote asserts that the letter was actually composed while Douglass was in Britain. Whether or not this was the case, the letter certainly reflects the themes which while in Britain defined Douglass’s internal struggles. In the letter, Douglass points to his growth since his slave life, and writes of his experiences with slavery through the self-conscious lens of his recent celebrity. He also deliberately presents an inaccurate account of Auld’s treatment of slaves, for which he latter apologized. Though he states, “I entertain no malice toward you personally,” he insists on turning Auld into an antislavery “weapon (336),” depersonalizing Auld as he was himself depersonalized, both as a slave, and as an antislavery orator. The letter is a bizarre, moving, and unforgettable document of the tensions within Douglass’s identity. It deserves far more scholarly study than it had received. Martin, Mind of Frederick Douglass, 6; My Bondage and My Freedom, (330-336).

[147] Blassingame, Frederick Douglass Papers, II:4 (February 2, 1847) (SOURCE).

[148] On March 4th Douglass ordered a return ticket on the Cambria , and was told that he would not be restricted to any part of the ship as he had been in his previous trip. But when Douglass’s attempted to board the ship in the beginning of April, he was told that his place had been given to a white passenger, and that he would not be able to eat his meals or mix socially with the first-class passengers. Douglass once again complied, but wrote several angry letters to British publications, and caused such a public uproar, that eventually he received a public apology from the owner of the ships, Mr. Cunard. Foner, Life and Writings, I:233 (April 3, 1847) (SOURCE); Quarles, Frederick Douglass, 54.

[149] Foner, Life and Writings, V:52 (April 29, 1847); Quarles, Frederick Douglass, 57; Fulkerson, “Exile as Emergence,” 82.

[150]Blassingame, Frederick Douglass Papers, II:60 (May 11, 1847) (SOURCE)1088.htm.

[151] McFeely, Frederick Douglass, 148.

[152] Cited in Quarles, Frederick Douglass, 58; McFeely, Frederick Douglass, 147 .

[153] Foner, Frederick Douglass, 77. According to Benjamin Quarles, there were 17 “Negro newspapers” published before the Civil War, and without exception, all “operated at a loss.” Four were in existence when Douglass decided to add his own to the list in 1847. The reasons for their unprofitability were varied. Chiefly, many of the poor black subscribers were unable to pay the subscription fees they pledged, and editors rarely had any backup capital. See Benjamin Quarles, Black Abolitionists, 86-89.

[154] Douglass, My Bondage and My Freedom, 305.

[155] Friedman, Gregarious Saints, 189-190.

[156] Cited in Robert Levine, Martin Delany, Frederick Douglass and the Politics of Representative Identity (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997), 18.

[157] Friedman, Gregarious Saints, 49. Friedman discusses the extent to which Garrison did indeed consider his abolitionist circle as a type of family, and suggests that it was the “loyalty, allegiance, and intense emotional warmth” toward Garrison that was the “fundamental source of Clique cohesiveness.”

[158] Quarles, Frederick Douglass, 59-67. New Lyme was an overwhelming success, while the crowd at Harrisburg turned rowdy, pelting Garrison and Douglass with stones and rotten eggs.

[159] Quarles, Frederick Douglass, 68.

[160] Merrill, Letters of Garrison, III:532 (October 20, 1847) (SOURCE); Foner, Frederick Douglass, 81; Tyrone Tillery, “The Inevitability of the Douglass-Garrison Conflict,” Phylon 37:2 (June 76): 143.

[161] Several scholars have classified this difference as one between Garrison’s dedication to radicalism and resilient absolutism versus Douglass’s pragmatism and willingness to compromise. See Tillery, “The Inevitability of the Douglass-Garrison Conflict; Quarles, Frederick Douglass, 74-75.

[162] Cited in Foner, Frederick Douglass, 76. See also “Our Paper and its Prospects,” from the first issue of The North Star, reprinted in Foner, Life and Writings, I:280 (SOURCE).

[163] Merrill, Letters of Garrison, III:533 (October 20, 1847) (SOURCE). The relationship between Garrison and Douglass deteriorated, especially after Douglass’s defection to political antislavery. By 1857, Garrison would call Douglass “one of the malignant enemies of mine” and in a sad measure of how much had changed, refused to go to England in 1860 because he knew that Douglass was already there. The two probably did not speak to each other after 1851. Quarles, Frederick Douglass, 78.

[164] Foner, Frederick Douglass, 83, Quarles, Frederick Douglass, 71.

[165] Stepto, Storytelling, 356. As with his original exile, the casualty in his departure was Anna, forced to move once again to a strange and alien place. McFeely, Frederick Douglass, 154.

[166] Gregory Garvey, “Frederick Douglass’s Change of Opinion on the U.S. Constitution: Abolitionism and the ‘Elements of Moral Power’,” American Transcendental Quarterly 9:3 (September 1995), 234-236. In My Bondage and my Freedom Douglass asserted that “But for the responsibility of conducting a public journal, and the necessity imposed upon me of meeting opposite views from abolitionists in this state, I should in all probability have remained as firm in my disunion views as any other disciple of William Lloyd Garrison (308).”

[167] Douglass, My Bondage and My Freedom, 308.

[168] Friedman, Gregarious Saints, 188; Pease and Pease, “Antislavery Ambivalence,” 686.

[169] Cited in Foner, Frederick Douglass, 94. Friedman, Gregarious Saints, 193.

[170] Merrill, Letters of Garrison, III:510 (August 16, 1847) (SOURCE). It seems likely that Douglass secretly recruited Delany for his paper when they met during his Western tour, without Garrison’s knowledge. The two men decided that Delany should concentrate on expanding the paper’s reader base, traveling throughout the western country and sending back accounts of his experiences. Delany remained an editor until June 1849. In his important book, Martin Delany, Frederick Douglass and the Politics of Representative Identity, Robert Levine attempts to demonstrate the importance of Delany’s participation, “obscured by Douglass and by biographers sympathetic to Douglass.” Levine, Martin Delany, 20. It is interesting however, to note that after his falling out with Garrison, Douglass’s relationships with other black abolitionists, like Robert Purvis, Charles Remond, and William Wells Brown, significantly deteriorated. A paper whose purpose was to unify American blacks around the image of their own self-sufficiency sadly failed to unite the black abolitionist community itself. Quarles, Frederick Douglass, 77.

[171] For all his expectations, Douglass was soon disappointed by the response of the black population to The North Star. By May 1848 the newspaper had five times as many white subscribers as black. Douglass attributed their “negative interest” “to the long night of ignorance which has overshadowed and subdued their spirit.” Cited in Foner, Frederick Douglass, 86.

[172] McFeely, Frederick Douglass, 150.

[173] Quarles, Frederick Douglass, 76. More problematic was the charge that Douglass was swayed by Smith’s financial support to cater to his political demands. However, an examination of the correspondence between Smith and Douglass reveals that their relationship was based more on a mutual appreciation than on financial patronage (though Smith did heavily finance the paper). McFeely, Frederick Douglass, 151.

[174] Foner, Life and Writings, V:186 (June 4, 1851) (SOURCE).