Ana Lucia Araujo on Objects as Archives Book Talk: The Gift: How Objects of Prestige Shaped the Atlantic Slave Trade and Colonialism

Article by Sebastian Ward (YC ’26), Gilder Lehrman Center Student Assistant

Edited by Michelle Zacks, Gilder Lehrman Center Associate Director

“Here I had to work with this possible trajectory for the object. This is what material culture can contribute to the work we do as historians. We can work in a way that is more free if we can consider all the possibilities of what we see.” Ana Lucia Araujo

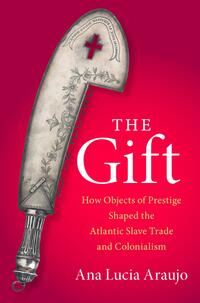

On January 29, 2024, in a talk sponsored by Yale University’s Department of the History of Art, Department of History, and the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition at the MacMillan Center, Ana Lucia Araujo discussed her new book The Gift: How Objects of Prestige Shaped the Atlantic Slave Trade and Colonialism (Cambridge University Press, 2024). Dr. Araujo, Professor of History at Howard University, was in conversation with Cécile Fromont, Professor of History of Art at Yale University.

Araujo’s book explores the role of luxury objects as central to negotiations between European traders and African rulers within the transatlantic slave trade. At the core of this work is the journey of an eighteenth-century ceremonial sword from France to Africa and back to France. A 1775 altercation off the coast in present day Angola between two groups of French traders provides key context for understanding the story of the sword. One group sought refuge with the Minister of Commerce in the African-controlled port of Cabinda, which was a part of the Kingdom of Nyogo at the time. A silver sword was commissioned in the port of La Rochelle, the second most important slave trading port in France, as a gift and a gesture of thanks to the Minister.

The French made several voyages to the port of Cabinda and around the entire region in search of enslaved Africans to purchase. Through spending time on the coast and in the Minister of Commerce’s house, they learned about what objects were perceived as valuable there, and the specific tastes of the Minister. Silver in particular was very valuable in both France and Africa. As Professor Fromont pointed out during the conversation, Araujo’s book is a corrective to the notion that enslaved people were exchanged for trinkets and things of little value.

Through careful study of a range of French, Portuguese, and English documents and artifacts, Araujo reveals how the exchange of prestige goods such as this sword became an element of how power and status were negotiated and contested. Within the long process of colonization and conquest of African states and armies by European powers, luxury items signaled a level of control exercised by local African rulers. This sword, Araujo suggested, is both a material object and “an archive of all the exchanges” that landed the sword in the Kingdom of Dahomey and, eventually, back in France.

According to Araujo, historians and anthropologists customarily have viewed gift-giving as a type of contract that places the recipient in a place of inferiority. However, Araujo emphasized that the process of giving and receiving gift items is part of a complex system of meaning-making. As she worked on the project, Araujo noted, the sources started to speak, including the object itself. As the object changed hands, its symbolic and material value shifted. “But an object of this kind, which was commissioned for a specific person, could have been used to please the individual,” she remarked. “It is not a static object, other people can have it. And the object changes, it could be melted and transformed into something else.”

The port of Cabinda, along with most other African trading posts North of the Congo River, was controlled by the Africans and not their European clients. In order to initiate trade, the Europeans would provide gifts for the authority figures there. Araujo explained that some gifts, such as textiles, guns, and alcohol, functioned as an element of commercial transaction as a currency or as a prescribed tribute or tax. Prestige items such as this sword, however, were methods through which the traders could gain the favor of African rulers and as such were designed to please the personal tastes of individual recipients. As Fromont noted, a luxury item like the ceremonial sword presents an answer to the question: “What do I give someone who has everything?”

Although distinct in its status, this object had an intrinsic connection with the other tangible objects Europeans used to buy people. It demonstrates how objects of luxury helped Europeans establish friendly business ties, so they could use common commodities in their home country to buy people, like textiles, iron bars, alcohol, and guns. “The gifts were not an attempt to convert to Christianity or for diplomatic exchanges, they were given to get an advantage in the African slave trade,” said Araujo.

Araujo highlighted the non-static nature of the sword. Not only was it in the hands of officials in the Kingdom of Nyogo, but also Dahomey, and then back to France. In tracing the history of this sword, Araujo found that slave traders transported it from Cabinda to Abomey, the capital of the Kingdom of Dahomey, after the first recipient died. In the late 19th century, French officers looted the item and brought it back to France, and in 2015, it appeared in a Parisian auction. There it was purchased by the Musée du Nouveau Monde in the French city of La Rochelle—the site of its manufacture—where it is on display. Throughout these exchanges, the character and the message encompassed within the sword changed as it passed from hand to hand. It vacillated between a symbol of gratitude, of power, and deceit. Each new recipient left a mark on the object.

“It looks like a story that the same people who gave the gift took it back after the recipient died,” says Araujo. “You give a valuable, special gift, then they die, then you take it to give it to someone else.”

Objects of prestige such as the sword were essential to the development of the transatlantic slave trade, and colonialism. The re-gifting and looting of the sword show that the Europeans traders were not seeking to make friends with the people they did business with but were looking to maximize profit in their ventures. They saw slaves as a pool of free labor and would later see Africa as a place to colonize to extract precious resources. No matter the angle of perception, gift-giving opened the doors of European-African relations, colonialism, and oppression.

Araujo points out that studying a manufactured object like the sword enriches our understanding of history in a way the written sources cannot. One point of the book is to demonstrate the value of studying material objects as a means for understanding the complexity of social relations and the ideologies that underpin them. This book, Fromont observed, helps reveal both the fullness of the archives and the “selective deafness” on the part of scholars about the range of source material that are considered as historical evidence.

Watch the full talk here: