Equal Terms

On January 29, 1864, a “large, well-formed and dignified man” stepped onto a “sort of rude balcony” at Grape Vine Point, where the Mill River meets the Quinnipiac. More than 1,000 Black men stood before him, gathered in front of a large garrison flag.

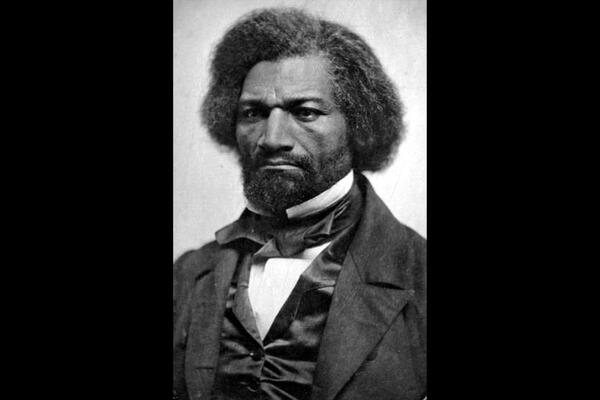

Frederick Douglass had come to address Connecticut’s first Black regiment in the Civil War. As Juneteenth approaches, his words offer a compelling lens to understand the meaning of the holiday—as do the actions of his listeners, who are much more closely connected to the first Juneteenth than one might expect.

Those men had been steadily arriving at Grape Vine Point since November 1863, forming the 29th Regiment, Connecticut Volunteer Infantry. So many people joined the encampment that they formed a second Black regiment, the 30th C.V. But despite the speed with which the regiment filled up, the soldiers stayed stuck at Grape Vine Point, delayed from marching for over two months because the military was moving slowly to appoint officers, who had to be white.

Douglass circa 1856

This context formed the backdrop for Douglass’s address to the assembled soldiers. “There is a difference between natural equality and actual equality,” Douglass said, “between theoretical equality and practical equality. Naturally we may be equal to the white man; in fact, we are not equal to the white man.” Whites, he said, had made the soldiers’ guns, bayonets, uniforms, caps, ships and the bridge to “span yonder stream,” and only among them was the training and experience to lead regiments. “I should like to see you commanded by black officers,” Douglass noted, once they had had the opportunity to acquire the requisite knowledge and skills.

The members of the 29th C.V. likely well understood the broader distinction Douglass was making. Even as Connecticut supported the Union’s war against the slaveholding Confederacy, it hardly embodied what Douglass called “actual equality.” Until recently, Black volunteers hadn’t even been allowed to muster. Now that they could fight, they were still to be segregated and paid less, all while enduring racism from many white peers and superiors. In battle, it would be worse: Black soldiers tended to have the most dangerous and undignified roles and faced worse treatment by the enemy when cornered or captured.

But Douglass saw the Civil War as an opportunity for Black Americans to change their stature and status, individually and collectively. “You are pioneers of the liberty of your race,” he said at Grape Vine Point. “With the United States cap on your head, the United States eagle on your belt, the United States musket on your shoulder, not all the powers of darkness can prevent you from becoming American citizens.”

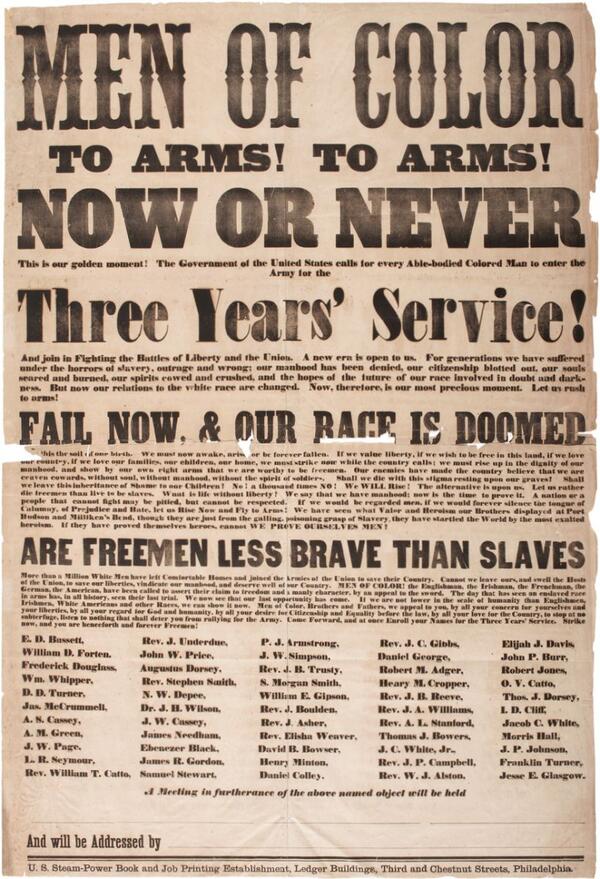

A recruitment broadside reportedly written by Douglass, published in 1863

Citizenship, Douglass understood, required action and access: in war, fighting to defend the Union; in peace, working with dignity for fair wages, educating oneself and one’s children in quality schools and voting with real political power—none of which were available to most Black people in either the North or the South. Contributing to victory in the war, in Douglass’s formulation, would provide the most compelling argument possible for turning theoretical equality into actual.

The origins of Juneteenth perfectly reflect Douglass’s distinction. The first Juneteenth celebration, on June 19, 1865, occurred after Union troops entered Galveston, Texas and informed enslaved people there that they had been emancipated. But legally speaking, they had been free since Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863—two and a half years prior. Only when Union troops arrived to enforce emancipation did freedom transform from a notion to a fact.

At the very same time, the 29th Regiment was on its way to Texas. The soldiers had fought in Richmond in April 1865, helping to break through Confederate lines in some of the last battles before Robert E. Lee surrendered. Even after the war ended, the 29th Regiment did not go home. Instead, soldiers made their way to Maryland and, on June 10, left with the 25th Corps of Texas to travel to the Lone Star State. On July 3, exactly two weeks after the first Juneteenth, the veterans arrived at Brazos de Santiago, at the southern tip of Texas, and then marched to Brownsville along the Rio Grande. Though there isn’t the documentation to detail their mission, it seems probable that their presence ended slavery in Brownsville in the same way Union soldiers proclaimed emancipation in Galveston.

Nearly 18 months before, when Douglass told the recruits that they were “pioneers of the liberty of their race,” he may not have anticipated such a literal truth.

Written by Steven Rome. Special thanks to the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition, whose research provided much of the basis for this article.