Writing to a Nation: Meena Kandasamy Talks Poetry and Resistance

“How do you write an intimate letter to your country?”

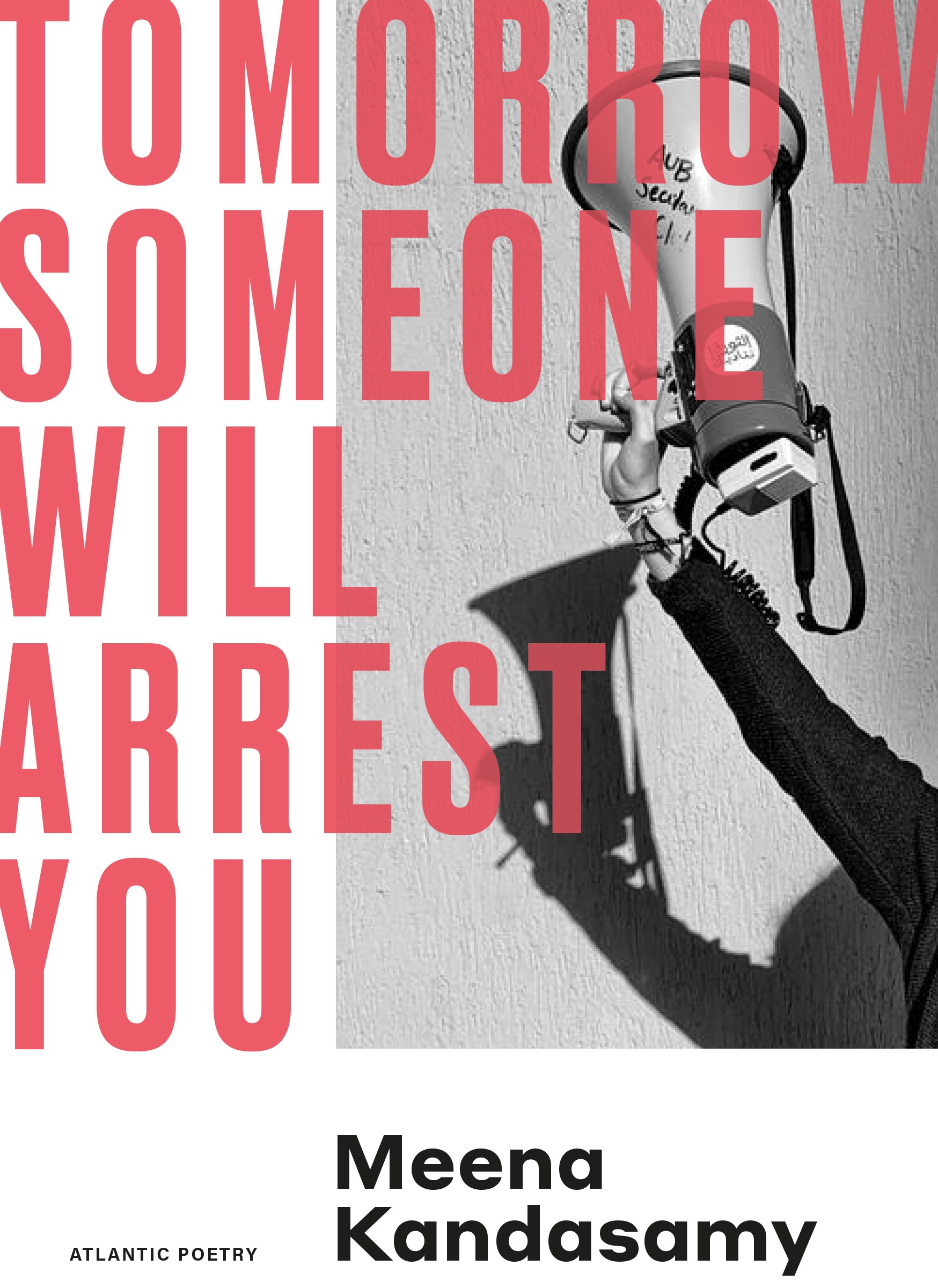

Poet and activist Meena Kandasamy posed that question as she discussed her latest published work, Tomorrow Someone Will Arrest You, in the Asian American Cultural Center on Wednesday, February 12th. The conversation was led by PhD student Nitika Khaitan and organized by the South Asian Studies Council. The event started with questions from Khaitan and poetry recitations before transitioning into an open discussion from the audience.

Kandasamy began by reading “In lieu of an artist statement, in lieu of a poem, in lieu of a diary entry.” The piece includes two moments she hopes to tell her future grandchildren about: a potential bride rejected for being “the kind of woman who reads Meena Kandasamy” and a fan who credited her writing with easing the process of coming out to a parent.

The anecdotes mark a central theme in Kandasamy’s work—the revolutionary potential of literature. Throughout the collection, she explores family relationships, caste tensions, gender dynamics and the evolving role of art as resistance. Compiled of poems written over a decade, Tomorrow Someone Will Arrest You moves fluidly between the personal and the political. For Kandasamy, that intersection is ever-familiar.

The book’s release in May of 2023 coincided with Narendra Modi’s campaign for reelection—a topic Kandasamy has long engaged with in her critique of the rise of Hindu nationalism in India. Much of Kandasamy’s work has focused on caste liberation, feminism and the intersections of literature and political resistance.

Kandasamy’s own family is of a lower caste, and she credits this background with shaping her literary and political consciousness. Mentioning her parents’ jobs as professors, Kandasamy emphasized their determination to complete higher education.

“When you happen to come from this kind of background, it becomes so important to claim the space to be an intellectual,” she said. “The first way they will render you useless is by saying you don’t have merit.”

With that understanding of systemic exclusion, Kandasamy’s father pushed her to pursue graduate studies. In 2010, she graduated with a PhD in Socio-linguistics from Anna University in Chennai, India.

Publishing in the U.S. and the U.K. became another way for Kandasamy to escape “the Brahmanical gatekeepers of knowledge” and the often hostile reception of her work in India. But Western validation was never Kandasamy’s objective, and gaining recognition outside of her country also came with its own complications.

She recounted a recent exchange with a student at Columbia University who attended a talk she held there. The student asked Kandasamy whether she ever imagined that she would one day be talking to Ivy League students. The question, though well-intentioned, underscores the perception that being welcomed in elite academic spaces in the West represents the pinnacle of success.

Kandasamy juxtaposed the interaction with a moment that actually felt like the height of her career. In 2016, she joined student protesters at the University of Hyderabad to participate in a hunger strike in response to the suicide of Dalit PhD student Rohith Vemula, who had faced institutional discrimination and was expelled from his university’s housing over his activism.

Kandasamy said she fasted with the students and read poetry as they protested, seeing firsthand how literature could serve as a political act.

“This is where my work finds meaning,” she recalled realizing.

Throughout the course of the talk, Kandasamy spoke about the personal stakes of political action—from the arrest of close friend and activist Rona Wilson, to her own experiences with the repression of dissent in India.

Speaking to her position as a woman in literature, Kandasamy said audiences often scrutinize women writers in ways that diminish their creative agency and literary skill. Noting how many characterize her novel When I Hit You as an autobiography despite her assertions to the contrary, Kandasamy criticized the tendency to conflate a woman’s fiction with her personal life.

“As a woman writer, you’re constantly consumed—you’re not read,” she said.

Kandasamy added that this erasure extends beyond contemporary literature and into the historical record, pointing to the absence of women in the field of Indian Classics.

“In 2000 years, there had never been a female translator,” Kandasamy said. So she became the second ever woman to translate the Tamil classic Tirukkuṟaḷ into English, calling her version The Book of Desire.

Like poetry, translation became an act of reclaiming space for Kandasamy. On Wednesday, she called the African American author Toni Cade Bambara’s claim that “The role of the artist is to make the revolution irresistible” her “manifesto.”

When Khaitan asked Kandasamy about the opportunity writing provides to “positively envision” our collective future, the author questioned whether writing can be anything but a response to the realities of the present. Reading from “The Discreet Charm of Neoliberalism,” she critiqued how the powerful co-opt language, stripping revolutionary words of their meaning.

By the discussion’s conclusion, Kandasamy’s question of how one writes about, against and, ultimately, to their country had come into clearer focus.

“Poetry stops, but one does not stop being a poet,” Kandasamy had read in her first recitation of the evening. Perhaps that artistic persistence is one answer to how literature can reckon with a nation’s injustices while imagining its future possibilities.

- Humanity

- Dignity