Children of Partition: Dr. Ali Usman Qasmi and Nida Mehboob on Healing Through Film

Two elderly brothers, Qari Farooq and Fazal Ahmad, sit across from one another in a bedroom—the one they shared in an orphanage in childhood. One begins to sing a song from those days and the other watches with a beaming smile and glistening eyes.

Their reunion, decades after being separated during the Partition of British India, is at the heart of Buhay Khulay Rakhi, a short film that grapples with the emotional aftermath of fractured families during Partition.

On Wednesday, March 26th, Dr. Ali Usman Qasmi of the Lahore University of Management Sciences and filmmaker Nida Mehboob came to Luce Hall to screen and discuss their recent film Buhay Khulay Rakhi, which traces the story of the two brothers separated during Partition and reunited decades later. The discussion was led by Palvasha Sahab, a PhD student in History at Yale.

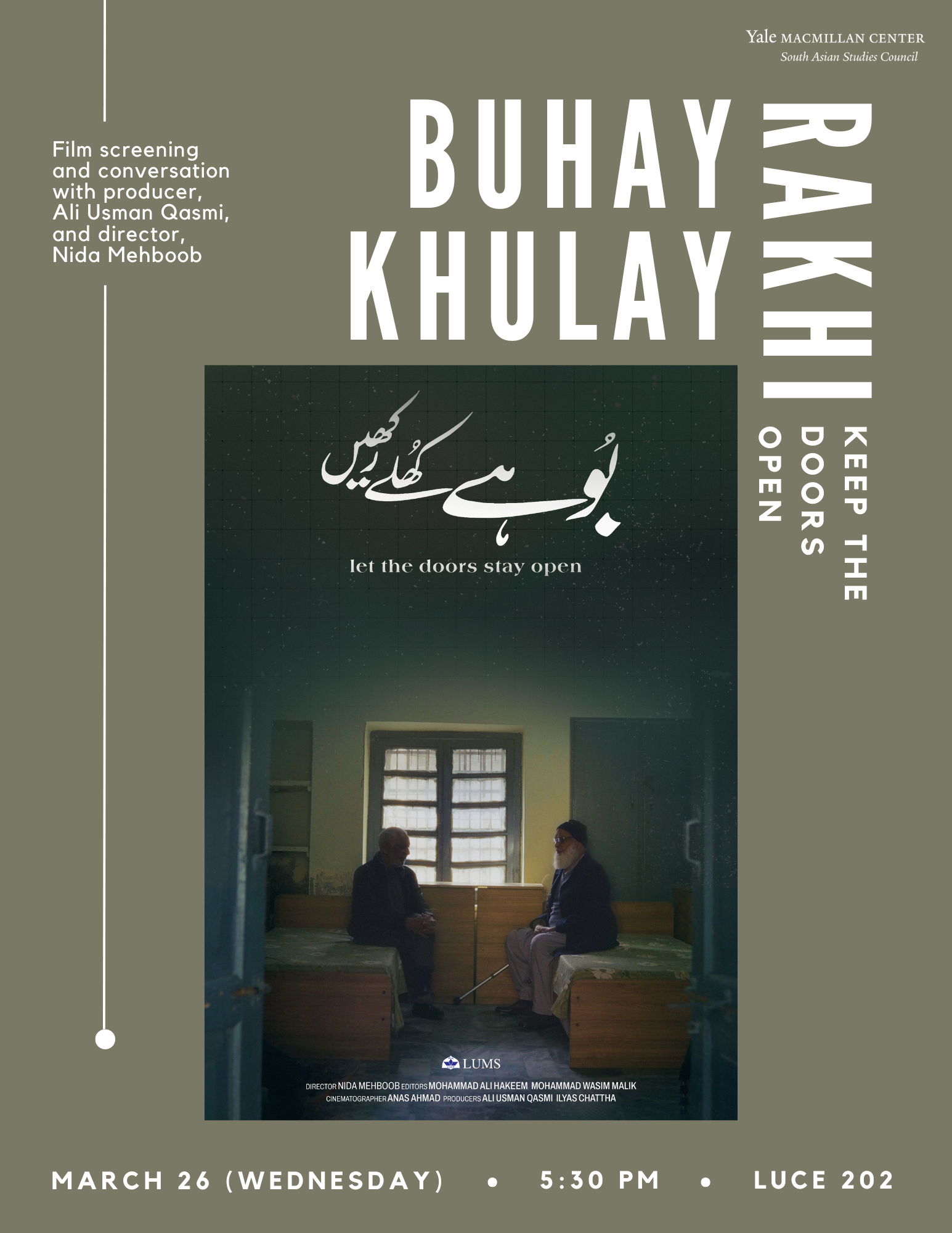

Event poster for the screening of Buhay Khulay Rakhi, held in Luce Hall on March 26, 2025.

“Buhay Khulay Rakhi,” Punjabi for “Keep The Doors Open,” alludes to the cultural and linguistic specificity of the region. Many survivors of Partition can only articulate their memories in Punjabi. Honoring that language, then, becomes a form of preservation in itself.

The film follows Qari Farooq and Fazal Ahmad. After their parents were forced to abandon them as they fled violence, they were adopted by Sikh and Dalit families. Filmed primarily in the Lahore shelter home where many children of similar backgrounds were housed, the documentary addresses displacement, loss, and the difficult process of healing for victims of Partition.

“Children are often neglected in this historical narrative,” said Qasmi. With this film, he hopes to change that.

Directed by Mehboob and co-produced by Qasmi and Dr. Ilyas Ahmad Chattha, the film includes archival footage of reunions and clips from YouTubers who have dedicated their channels to reuniting families separated by Partition.

“Citizen historians have done a fantastic job of documenting these stories,” said Qasmi. “What the state narrative is unable to accommodate is being provided by community historians.”

Qasmi added that these creators are changing what it means to be a historian, noting that they often do a better job than even academics—in part because they create narratives rather than simply archiving dates and documents, bringing emotional resonance to historical fact.

For Qasmi, literary and visual imaginations “are the ones in which you’re able to understand the pathos of partition.”

“It’s only through animating these statistics of these documentations into a visual medium or some fictional form that you can get the sense of the experience,” he said.

Mehboob, who had full creative control over the film, made that vision of embodied memory and emotional truth materialize.

Her creative direction centered the brothers’ experience while framing it within the context of the larger history of family separations due to Partition. The film includes minimal background music or voiceover, forcing viewers to sit with each silence, gesture, and glance exchanged between the reunited siblings.

Qasmi praised Mehboob’s inclusion of scenes of reunification, highlighting their simplicity and power.

“You can clearly see that these are children of the same parents who ended up on different slides of the border,” he said.

Mehboob brought that same quiet intensity to scenes with the two brothers. Close-up shots, like that of a trembling hand, seem to capture the weight of decades lost in single moments. Speaking to her emphasis on the orphanage, Mehboob said she aimed to use it “as a site of evidence and of memory.”

The team only had one day to film in the orphanage, and Mehboob made sure to utilize the space to evoke the emotional and spatial connection between the brothers. The pair naturally gravitated toward the same room where they used to live. There, they discussed their memories of the space.

Mehboob characterized the process of reunification as “healing,” noting its importance in both an emotional and political sense.

“I think that’s [healing’s] the highest form of psychological resistance that one could have,” she said. “Just the fact that they’re sitting in the same room that might have been traumatizing for them and are just able to sing or laugh—for me, that was resistance.”

Notably, the film ends with a shot of an incomplete monument—suggesting that healing is still ongoing and that historical reckoning is not yet complete.

Qasmi said that more documentation, acknowledgment and storytelling is necessary for that healing to take root.

“The state narrative in Pakistan is that of erasure, or if there is remembrance, it is through the lens of sacrifice,” he said.

Instead, Qasmi emphasized the importance of confronting the enduring wounds left by Partition to create a more compassionate future.

When asked what he envisions for a world wherein we might “do better” for future generations of children, Qasmi referred back to the film’s title.

“Keep the doors open, I think that’s all we can say,” he began.

Continuing, Qasmi said that there is already a “growing disconnect” from Partition among today’s youth. That disconnect, he noted, is good if it means moving beyond inherited trauma but dangerous if it results in abandoning the past entirely.

“The more people are allowed to meet and interact and realize how similar they are…that will help create the intimacy we need for our children,” Qasmi said.

In Buhay Khulay Rakhi, that commitment to reunification manifests in a story of two brothers that rekindles hope for a future where no child’s Partition story is forgotten.

- Humanity

- Societal Resilience