Memory & Mourning: Living Without Closure

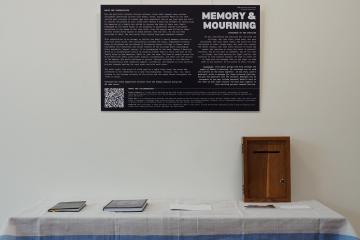

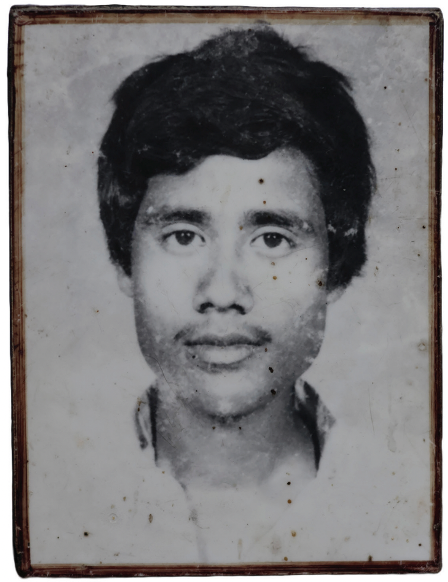

If you walked into the Luce Hall Common Room at Yale’s MacMillan Center sometime between February 13th and 18th, you would have noticed a small installation on the south end of the room. It was a table covered by a linen white and blue cloth. Atop it was an assortment of books, a stack of postcards, some pens, and a wooden box. Upon first glance, the installation was inconspicuous, but upon reading the descriptive poster that hung above the table, it became somber and powerful. It read, “Memory & Mourning attempts at chronicling the memories of a family who failed to recover the body of their son, Khagen Das, popularly known as Babli, kidnapped by a death squad in the backdrop of heightened counter-insurgency operations in the Assam of the late 1990s.” The installation confronted viewers with this painful history, asking the question: can one really find closure from such unhealed trauma?

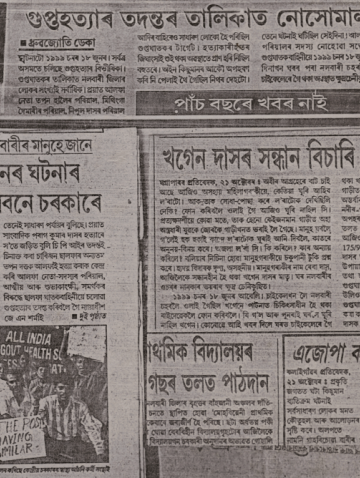

The installation was a product of collaboration between Dixita Deka, a Postdoctoral Associate in Agrarian Studies at Yale’s MacMillan Center from Assam; Biswajit Thakuria, a visual artist from Assam, and Dipika Das; Babli’s older sister from Nalbari in Assam. One of the books on the table–a bound copy of an essay written by Deka and published by feminist publishing house, Zubaan, titled “Suppressed Silences: Women as Witnesses and the Wounds of Witnessing Secret Killings in Assam”–invited viewers to learn more about the legacies of the violence which took place through academic readership. Placed beside “Suppressed Silences” was another book titled Memory & Mourning, a collaborative effort to visually represent Babli’s story and the reverberations of his death experienced by his family. The book pulls disparate documents together to try to reconcile with an untimely death, to mourn an unrecovered body. The book is abstract, like a tragic scrapbook of scans of reports, letters, photographs, quotes from his family, and excerpts of writing.

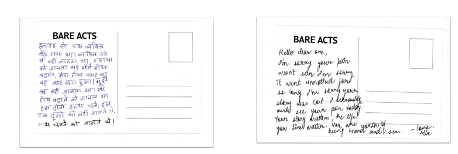

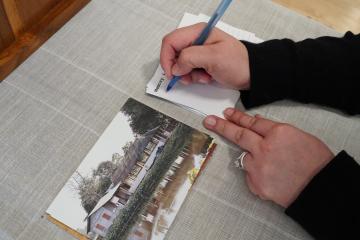

Next to the books was a stack of postcards, a pen, a wooden mailbox, and a pamphlet titled “Postcards to the Families.” The inclusion of postcards follows an installation previously mounted by Deka and Thakuria at the Prameya Art Foundation in New Delhi from December 2023 to January 2024 titled In the Shadows of Silence. That installation featured a display of animated landscapes in Assam to evoke collective mourning and provided an opportunity for participants to write postcards to the families of those killed.

The “Postcards to the Families” pamphlet featured images of postcards submitted by visitors to the Delhi installation. These postcards are written in various languages, by people from all sorts of geographies and backgrounds. There was great power in seeing handwritten notes from all corners of the world, reaching out in mourning, with sincerity from their souls. The postcards in this pamphlet served as inspiration to the participants at the MacMillan Center who picked up pens to write their own messages.

Viewers both in Delhi and New Haven were prompted by an instructional statement, written by Dixita and her collaborator Biswajit Thakuria, reading: “We met individuals and families who survived the killings, who lost their loved ones…who lost their ability to think and speak, who do not want to remember, who do not want to forget, who continue to live without closure. We hope to reach out to them with the message that we see them, we keep them in our prayers, we are proud of their courage.”

On February 18th, Dixita Deka gave a talk at the SASC Colloquium titled “Living Without Closure: Memories in the Aftermath of Insurgency” that elaborated on the secret killings in Assam during the late 1990s and gave important, sobering context for the installation on view at the MacMillan Center.

Deka began her talk by outlining Assam’s historical struggle with state violence and insurgency. The United Liberation Front of Assam (ULFA), founded in 1979, emerged as a separatist movement seeking Assam’s sovereignty. Its membership, initially composed of agrarian youth, expanded in the 1980s when cadres trained abroad and, by 1989, began recruiting women. Counter-insurgency efforts escalated in 1990 with Operation Bajrang, leading to widespread militarization and reports of human rights abuses. In the late 1990s, secret killings targeted families of ULFA members, creating a climate of fear and silencing dissent.

Deka recounted the story of Barsha (pseudonym), whose uncle and family were killed in one such attack.Their home was destroyed in an explosion, and Barsha vividly described recovering their bodies. A memorial, unnamed and unfinished, was later built at the site, featuring a sculpture and a funeral pyre. Seeing this memorial inspired Deka’s investigation into how families navigated the long-term aftermath of these killings.

Deka’s research examines Assam’s secret killings (1998–2001), a campaign of extrajudicial murders targeting ULFA-affiliated families under the guise of counter-insurgency. Through firsthand narratives, she explores how women—both survivors and former ULFA members—navigate the aftermath of state-sponsored violence. Her work, spanning journalism, scholarship, and artistic installations, challenges the silence surrounding these events, demanding justice and recognition for those still seeking closure. Approaching these events through the lens of memory, grief, and resistance, Deka highlights the enduring psychological and social impact of these killings.

The secret killings gained public recognition in 1998 when journalists discovered a severed human leg, leading to multiple inquiry commissions. Survivors like Ananta Kalita identified members of the death squads, exposing collaboration between surrendered insurgents, the military, and police. Deka described how these killings were both secret and public, with the state neither fully denying nor acknowledging its role. The only published academic book on the subject, Secret Killings of Assam: The Horrific Story of Assam’s Darkest Period by Kaushik Deka, Mrinal Talukdar, and Utpal Borpujari, primarily reproduces the government’s officially commissioned report. Fictional works, such as The House with a Thousand Stories by Aruni Kashyap, offer another way to access these traumatic histories, but the publications that tell the stories of the secret killings are few and far between. Deka’s work fills a crucial gap by seeking out lived narratives, recording oral history, and preserving truth.

Deka discussed the complexities of memory and violence, noting the absence of an official scholarly term for such horrors. She distinguished between power and violence, emphasizing how legitimacy shapes their perception. Her research does not focus on identifying perpetrators but rather on the institutions and structures that enabled these killings. She sought to understand how different groups remember the violence: civilians recall abducted youth and abandoned homes; journalists recount the trauma of witnessing state brutality; insurgents and police offer conflicting justifications.

Addressing the possibility of closure, Deka noted the absence of reconciliation commissions, formal acknowledgments, or significant compensation. Resistance took shape in the form of martyrdom—families using the bodies of victims as symbols of protest. Police often warned survivors that they could only reclaim a body if they refrained from protesting. In some cases, families held cremations without the physical remains, with nothing to rely on for solace. The government as well as ULFA issued certificates recognizing victims, though these documents often implied insurgent affiliation, complicating their significance.

Presenting Memory & Mourning at Yale, in collaboration with the MacMillan Center and the South Asian Studies Council, was significant to Deka, as it placed Assam’s history within a broader conversation on human rights violations. The discussions that followed her talk intersected with stories of political violence from other conflict zones, creating an immediate connection between Assam’s history and shared experiences of grief and resistance.

Deka noted that academic research is often confined to a specialized audience, restricted by theoretical frameworks and disciplinary language. Reflecting on the project, she shared, “My experience of working with my collaborator, a visual artist, has offered me the freedom to perceive the project creatively and also in a way accessible to people outside academia and across disciplines. The installation offered a way to tell the narratives from the field through photographs as well as through prose which need not necessarily incline towards any rigid academic framework. The experiences which words could not capture, the visuals did.”

Deka endeavors to work against traditional academic approaches to research which risk extracting data without providing tangible support to survivors. She remains conscious of her responsibility, making an effort to stay connected with families, particularly on anniversaries of their loved ones’ deaths. Closure remains elusive for these families. In the absence of justice, the act of remembrance—through art, storytelling, and community rituals—serves as a form of resistance against erasure.

- Humanity

- Societal Resilience

- Dignity