Agricultural Climate Resilience and Adaptation in Puerto Rico

Allegra Lovejoy Wiprud, Yale School of the Environment

Summary

I undertook a short research trip in Puerto Rico in January 2019 to study agricultural climate resilience and adaptation. I explored questions of economic resilience, resilience to extreme weather exacerbated by climate change, and the impact of government policies on farmers’ and land managers’ adaptation choices.

During this trip, I met with five land managers from the eastern, central, and western parts of the island including four farmers and one forest preserve manager. The land managers’ resilience and adaptation needs varied greatly based on the type of farm/enterprise, location, and access to resources. However, there were common themes, such as major disruption during and after the 2017 hurricane season; managing for heavy rains and wind conditions; self-sufficiency; and inadequate governmental support.

What is the context in which these land managers operate? Agriculture in Puerto Rico supports less than 15% of the island’s food supply. Thus, farmers can expect a steady market for their products. Agriculture in Puerto Rico primarily takes the form of hundred-acre plantations of banana, plantain, or sugarcane; large livestock operations; and small family farms under 15 acres. These small family farms are either a primary source of sustenance for households or are a ‘family garden,’ supporting a family that primarily earns from other employment. In either case, small family farmers frequently work under high resource constraints.

The agriculture sector has seen a resurgence of interest since a food movement began in approximately 2013. Many young people who had left the island or had grown up elsewhere returned to Puerto Rico to revive family farms or start new farms. The new food movement was more focused on diverse production, heritage crops, and organic farming than the dominant agricultural scene at the time.

With respect to the forest preserve manager, her project is one of very few active timber operations on the island. Thus, market structure or government support for a Puerto Rican timber industry do not exist.

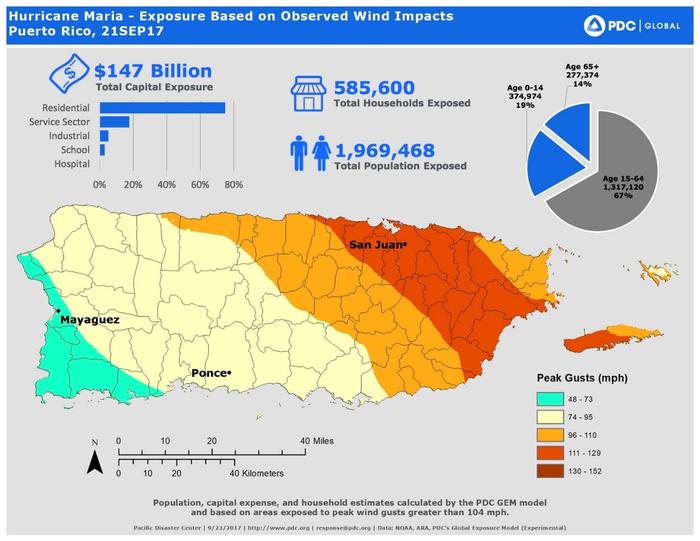

However, the 2017 hurricane season left substantial damage in the agricultural sector, undoing many of the gains that had been won in local food production. For months after Hurricane Maria, which hit Puerto Rico in October 2017 as a Category 4 storm, almost all of the island’s food was imported. Many farmers experienced a partial or total crop loss.

Aboveground crops such as grains, bananas and plantains were destroyed in the winds. However, native root crop starches, typically grown in home gardens, remained available. Farmers growing coffee, fruit, and other trees lost the year’s production due to winds and had damage to many trees as well. Most farmers also experienced structural damage of some kind. Damages were greatest in the Eastern portion of the island which experienced the heaviest winds as well as in areas with soils saturated by Hurricane Irma, which passed just weeks beforehand. Thus, post-storm, they contended with loss of their current harvest; a need to replace perennial trees and plants; and repairing structural damage.

Image: Pacific Disaster Center, https://reliefweb.int/map/puerto-rico-united-states-america/hurricane-ma…

The struggle to replace these losses was exacerbated by road damage and unavailability of power and communications for weeks and, in some cases, months. This created a struggle to obtain the most basic supplies – including livestock feed – for farmers and other rural communities and city dwellers. Access to markets was also highly limited.

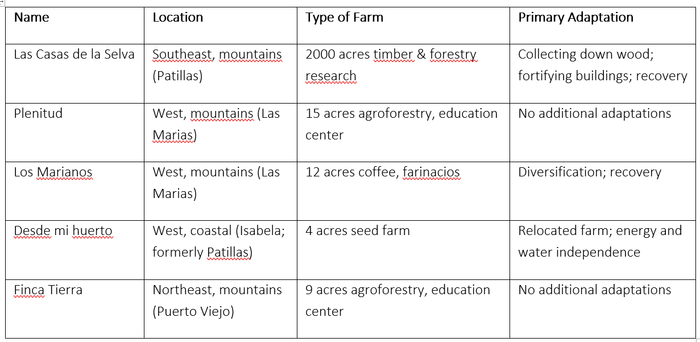

The experiences of individual farmers, of course, varies. Among the farmers I met, differences in land management strategies and crop choices, as well as geography, affected their experience in the 2017 hurricane season. Their climate adaptation strategies also vary. These findings are summarized in the following table:

For example, the farms with an agroforestry model experience minimal damage during rainy seasons, droughts, and severe storms, in part due to their water management strategies, erosion control strategies, food and water self-sufficiency, and on-farm resource availability. For the most part, their current adaptation and resilience strategies focus on increased resilience of structures as well as increased food storage and energy self-sufficiency. They did not report additional efforts in farm management towards adaptation.

Farms that were in conditions prone to damage (such as non-stabilized soils in the Eastern and Western mountains) deal with landslides and down trees during severe storms and rainy seasons. They continue to focus on recovery efforts 15 months after Hurricane Maria including replanting trees and other crops, collecting down wood, and repairing buildings and roads, or in the case of one farmer interviewed, relocating entirely. They express interest in additional water management and erosion control techniques, but all expressed a limitation of capacity to research these methods, let alone implement them, due to continued recovery efforts.

Las Marias

In Las Marias, a township in the mountains of the Western part of the island, I visited two farms. Plenitud and Los Marianos are neighboring farms in this rural area. Plenitud was established about ten years ago by a young couple returning to Puerto Rico from Florida with the goal of creating a farm and educational center to have an impact on the lower-income Western part of the island. Los Marianos is a third-generation small family farm that relies on coffee as a cash crop, some livestock, and farinacios.

In Las Marias, a township in the mountains of the Western part of the island, I visited two farms. Plenitud and Los Marianos are neighboring farms in this rural area. Plenitud was established about ten years ago by a young couple returning to Puerto Rico from Florida with the goal of creating a farm and educational center to have an impact on the lower-income Western part of the island. Los Marianos is a third-generation small family farm that relies on coffee as a cash crop, some livestock, and farinacios.

Plenitud experienced minimal damage during the 2017 hurricane season. Apart from the expected down branches, crop top loss, and some erosion, they did not experience landslides, down trees, or structural damage. Their recovery efforts mostly consisted of clearing down woody debris, replanting seasonal crops, and re-establishing access to supplies. Their practice of bulk purchasing food supplies and storing them in a secure pantry enabled them to feed themselves and neighbors. Resilient natural buildings made with earthbag construction also provided shelter for the farm team. As a nonprofit, donations received after Hurricane Maria helped them repair damage on their own property and help others.

Plenitud reported significantly increased interest in its resilient natural building workshops and agroforestry workshops. Approximately 25% of attendees in the former said they had lost their homes during Hurricane Maria, and more than 50% of attendees in the latter said they had experienced landslides and crop loss during that storm or other storms. I asked Plenitud’s construction manager whether government regulations were an obstacle to earthbag construction. “Not really,” he said. “For small outbuildings, it’s not an issue. For buildings intended to be residences, you do need the drawings to be certified by an engineer. We’re working on that right now.”

By contrast, their neighbor, Los Marianos, a low-income family farm on a steeply sloped hillside, experienced substantial landslides and damage to their coffee crops and farinacios. Due to the bushy nature of arabica coffee, the trees do not tolerate high winds. Mariano and Jochi reported that all the coffee trees were either killed or damaged and will need eventual replacement. The loss of the year’s coffee crop was especially painful as they were only a few weeks from harvest time. They have started replanting coffee robusto, a larger tree that is more wind-tolerant and may better withstand landslides. Another adaptation strategy is to increase their vegetable production. These crops are easy to sell, they say, and also yield within 40-60 days, meaning that if they experience another major weather-related disturbance, they can redevelop an income stream much more quickly than by waiting for the 9-month farinacios or the 3-year coffee. The farmers were able to obtain an NRCS matching grant to subsidize the cost of their new high tunnel.

By contrast, their neighbor, Los Marianos, a low-income family farm on a steeply sloped hillside, experienced substantial landslides and damage to their coffee crops and farinacios. Due to the bushy nature of arabica coffee, the trees do not tolerate high winds. Mariano and Jochi reported that all the coffee trees were either killed or damaged and will need eventual replacement. The loss of the year’s coffee crop was especially painful as they were only a few weeks from harvest time. They have started replanting coffee robusto, a larger tree that is more wind-tolerant and may better withstand landslides. Another adaptation strategy is to increase their vegetable production. These crops are easy to sell, they say, and also yield within 40-60 days, meaning that if they experience another major weather-related disturbance, they can redevelop an income stream much more quickly than by waiting for the 9-month farinacios or the 3-year coffee. The farmers were able to obtain an NRCS matching grant to subsidize the cost of their new high tunnel.

I asked Mariano whether he had faith that these adaptation measures would be enough to ensure a resilient farm. “No tengo el fe,” he replied immediately. No, he doesn’t have faith that the farm will be resilient or provide them steady income, or that even the coffee robusto will be fully storm-tolerant. He also acknowledged that given the low price for coffee and the high amount of labor required, they barely made any money on the crop. “But what can I do?” he said. He and his brother did not want to abandon their parents or the family farm. Better, he said, to plant the farm and tend the farm, even if it all gets washed away again, rather than to leave it fallow.

A comparison of the experience of Plenitud and Los Marianos reveals potential room for adaptation towards resilient natural buildings as well as towards terrace or contour farming. Plenitud’s resilient natural buildings did not suffer damage during the 2017 hurricane season, while many other concrete or wooden structures on the island did. Plenitud’s practice of terrace farming stabilizes hillsides against landslides through reducing area of steep slope and restricting cultivation to level areas, while contour planting uses strong-rooted vegetation to hold soil in place. Finca Tierra, another farm with a similar approach as Plenitud, reports similar resistance to landslides during periods of heavy rain, even though it is on the opposite, wetter, side of the island.

Isabela

I visited one farm in Isabela, a coastal township in the northwest corner of the island. This farm, Desde mi huerto, produces seeds on four acres. The farm is the only certified organic seed producer on the island. Its founder, Raul Rosado, says he shares the 2013 food movement’s vision of local food sovereignty. Raul’s founded his farm in Patillas twelve years prior. The humid conditions there, he said, were a challenge with the necessity of cold, dry storage for seeds. While he already had a plan to relocate the farm, crop loss and down trees in the 2017 hurricane season made this a necessity. As his seeds were stored in a secure storage container, he did not lose his main source of income, but the farm itself received substantial damage.

I visited one farm in Isabela, a coastal township in the northwest corner of the island. This farm, Desde mi huerto, produces seeds on four acres. The farm is the only certified organic seed producer on the island. Its founder, Raul Rosado, says he shares the 2013 food movement’s vision of local food sovereignty. Raul’s founded his farm in Patillas twelve years prior. The humid conditions there, he said, were a challenge with the necessity of cold, dry storage for seeds. While he already had a plan to relocate the farm, crop loss and down trees in the 2017 hurricane season made this a necessity. As his seeds were stored in a secure storage container, he did not lose his main source of income, but the farm itself received substantial damage.

The choice of Isabela provided Raul with a drier coastal location more sheltered from seasonal winds. He was able to meet his basic self-sufficiency goals through choosing a site with access to an irrigation canal and installing rooftop solar to ensure the seed container remained cool regardless of the municipal power grid. Raul was able to obtain an NRCS matching grant to subsidize the cost of his new greenhouse on the new property.

Patillas

Patillas is a township near the Southeastern most part of the island on the first mountain range that rises from the ocean. Eye on the Rainforest/Tropical Ventures is a 2000-acre forest preserve in this area, covering several hills in which are the sources of three local watersheds. I met with Thrity Vakil and Andres Rua, the site managers. Established in 1980, Tropical Ventures was able to obtain an unusually large parcel of land as an NGO dedicated to forest conservation and watershed protection. The NGO’s work is dedicated to promoting natural forest regeneration methods and reviving the island’s timber industry through research, demonstration, and timber production. Over the site’s 40-year history, its managers have extensively documented forest growth, planting, and harvesting, resulting in several peer-reviewed publications, and have developed a lively wood furniture and flooring business. For several years they encouraged other land managers to join them in building a timber industry in the island, but shared that they did not meet with success.

Patillas is a township near the Southeastern most part of the island on the first mountain range that rises from the ocean. Eye on the Rainforest/Tropical Ventures is a 2000-acre forest preserve in this area, covering several hills in which are the sources of three local watersheds. I met with Thrity Vakil and Andres Rua, the site managers. Established in 1980, Tropical Ventures was able to obtain an unusually large parcel of land as an NGO dedicated to forest conservation and watershed protection. The NGO’s work is dedicated to promoting natural forest regeneration methods and reviving the island’s timber industry through research, demonstration, and timber production. Over the site’s 40-year history, its managers have extensively documented forest growth, planting, and harvesting, resulting in several peer-reviewed publications, and have developed a lively wood furniture and flooring business. For several years they encouraged other land managers to join them in building a timber industry in the island, but shared that they did not meet with success.

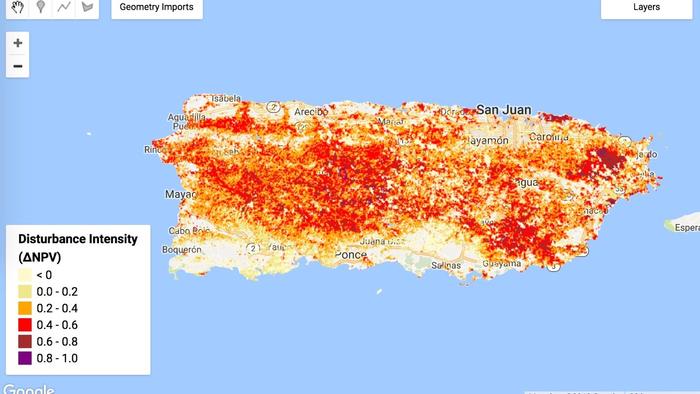

This map of Puerto Rico shows highest forest damage and tree mortality impact areas in with darker tones of red indicating more intense forest disturbance as tree mortality and crown damage. Grey areas represent non-forested areas or areas with cloud cover. Image: Berkeley Lab, https://newscenter.lbl.gov/2018/03/01/assessing-impact-hurricanes-puerto…

The 2017 hurricane season caused extensive damage to the forests of the Patillas region, including at Eye on the Rainforest. As the first mountain range rising from the ocean, this ridge took the greatest hit from Hurricane Maria, following Hurricane Irma which saturated soils. As a result, forests took extensive crown damage from winds as well as a great deal of tip-over due to soil saturation and winds. The homestead at Eye of the Rainforest also sustained substantial damage to structures, the tree nursery, and roads. The site manager, Thrity, told me that it took her team weeks with chainsaws to clear the roads to be able to get in and out of the property. They are still unable to access parts of the forest due to woody debris on roads. Power and phone service were not restored to the area until six months after Hurricane Maria. Steep, erosive slopes are also an issue of concern; landslides occur each year during the rainy season.

Since that storm, the small team has been entirely focused on survival, clearing woody debris, repairing structures, and salvaging wood. That project has taken their efforts far beyond Eye of the Rainforest itself to engage in policy advocacy around natural resource management. Following the storm, down wood around the island was sent to landfills and chipped, including hundred-year-old trees with timber valued in the thousands of dollars. Thrity and Andres dedicated weeks and months of advocacy to have the timber stored and salvaged for public or commercial use within the island. Although their advocacy achieved a temporary injunction to have the wood stored, the injunction was allowed to expire after the wood was certified of no value by marine biologists sent as inspectors by the Department of Natural Resources. Tens of thousands of dollars worth of wood were chipped and sent to landfill. Thrity and Andres were vocal about the need for policy changes to support salvage of down wood, as well as more robust financial support for Puerto Rican land managers via NRCS matching-grant programs, which currently cannot meet the demand. They were also vocal about the need for greater applied science and greater engagement on behalf of the staff of the Department of Natural Resources in Puerto Rico, and for greater support for home-grown industries in Puerto Rico – rather than simply export industries – on behalf of the USDA as a whole.

As far as climate adaptation strategies, Thrity is working with architecture students from the University of Puerto Rico to rebuild stronger structures. They already have solar panels, food storage, a gravity greywater system, and their own well. Otherwise the team is making no additional efforts adaptation. However, clearing of down woody material remains an ongoing effort.

Conclusion

In conclusion, climate resilience and adaptation measures among land managers in Puerto Rico vary based on location, topography, vulnerability to storm season damage, and financial resources. In general, I found that land managers who implemented water management practices such as terracing, contour planting, and maintaining perennial groundcover were less susceptible to landslides and crop loss than those who did not attend to slope stabilization. Choice of building materials and style was also an issue affecting the resilience of structures during extreme weather events. The financial ability to establish independent energy and water sources such as solar panels, wells, greywater systems, and rainwater capture also made a difference in the adaptive resiliency of sites, as did the financial ability to rebuild damaged structures and replant crops even with a lost cycle of income. However, climatic variations due to topography and moisture regimes also strongly affect site conditions and site outcomes during rainy seasons. Adaptation measures should take into account these local conditions with special attention to appropriate water management practices.