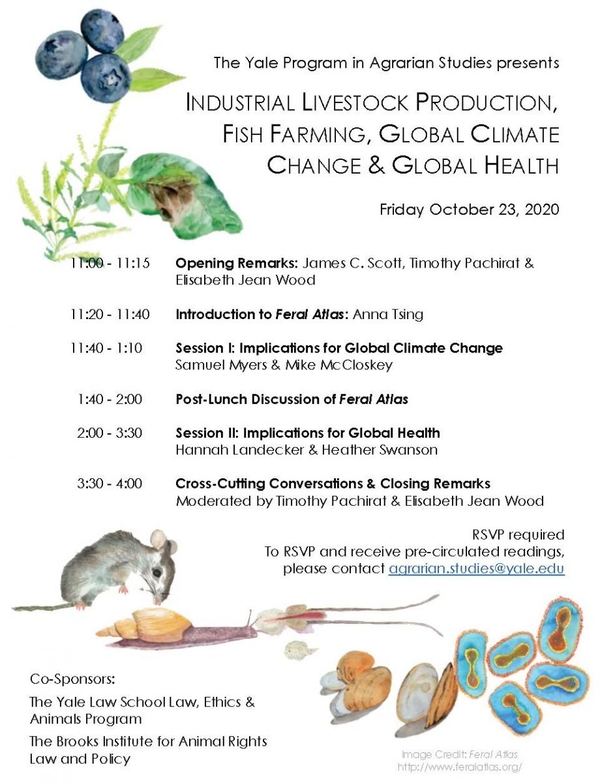

Industrial Livestock Production, Fish Farming, Global Climate Change, and Global Health

On October 23, 139 people Zoomed in to the conference Industrial Livestock Production, Fish Farming, Global Climate Change, and Global Health. Sponsored by Yale’s Program in Agrarian Studies and the Yale Law School’s Law, Ethics, and Animals Program, the conference brought together scholars from several disciplines as well as practitioners to discuss how industrial livestock and fish production contribute to global climate change and global health crises.

Jim Scott, Sterling Professor of Political Science and Professor of Anthropology at Yale, gave the opening remarks, which focused on how the domestication of animals has massively transformed landscapes, particularly in the last 100 years, leaving little trace of the pre-Anthropocene world.

The global premiere of the interactive platform Feral Atlas: the More-than-Human Anthropocene followed, led by Distinguished Professor Anna Tsing of the University of California at Santa Cruz, editor and curator of the Atlas, along with Jennifer Deger (James Cook University), Alder Keleman Saxena (Northern Arizona University) and Feifei Zhou (Aarhus University). The Atlas argues that “critical description of the Anthropocene, that is, theoretically informed empirical attention to the anthropogenic transformation of land, air, and water, is a central task for our time.” Drawing on several dozen “field reports” from the biological sciences, environmental studies, ecology, anthropology, history, critical race theory, decolonial studies as well as poetry and the arts, the digital project takes a radically interdisciplinary approach to explore the relationship between the non-human and human Anthropocene. Professor Tsing led the audience through several different layers of the Atlas, introducing audience members to the project’s different components and encouraging them to explore and play with Feral Atlas and find their own paths through the website.

In the first session of the day (moderated by Sarah Pickman, doctoral student in the History of Science and Medicine), Samuel Myers, Senior Research Scientist at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and Director of the Planetary Health Alliance, illuminated the double nutritional challenges of malnutrition and metabolic diseases facing the planet’s growing human population. He argued that these challenges are intensified by climate change and other large-scale anthropogenic environmental changes. Myers identified the reduction of waste, adoption of more plant-forward diets, and technological innovations such as precision agriculture as the most hopeful routes towards meeting these nutritional challenges while freezing or reducing agriculture’s current carbon footprint. Mike McCloskey, founder of the dairy cooperative, Select Milk Producers, and the nation’s largest agritourism attraction, Fair Oaks Farms, then offered a tour of his large-scale Midwestern dairy farm and identified several technological innovations he helped pioneer at Fair Oaks, including implementation of feed rations that greatly reduce enteric methane emissions from cattle and the transformation of manure into energy, clean water, and organic fertilizers. These innovations, McCloskey argued, will be capable of bringing dairy’s greenhouse gas footprint to net zero within five years for early adopters and by 2050 for dairy in the United States as a whole.

After a short break for lunch, the afternoon’s activities began with a discussion session on Feral Atlas, during which Anna Tsing answered questions from the audience about the project. Symposium attendees - including the other presenters - had many questions, ranging from the practical logistics of creating a large-scale digital humanities project, to conceptual questions about the organization of the Atlas.

Afterwards, the second session of the day (moderated by Caroline Parker of the Law School’s Law, Ethics and Animals Program) began with a talk by Hannah Landecker, Professor at the University of California at Los Angeles and Director of the UCLA Institute for Society and Genetics. Landecker drew from her research on the history of metabolic science in the United States, focusing on how animal metabolism became the object of intense study by agricultural scientists in the twentieth century. These agricultural experts, Landecker argued, understood livestock as a metabolic machine for converting plant-based proteins into animal-based food products to feed the growing American population. Over the course of the twentieth century, the “industrialization of metabolism,” occurred, she argued. Livestock were initially fed waste products from other agricultural processes, and later antibiotics, vitamins, amino acids, and enzymes to enhance their bodies’ metabolic processes (compounds that were themselves the result of metabolic processes of fungi and yeast). Heather Anne Swanson, Associate Professor at Aarhus University, then discussed the history of industrialized fish cultivation practices. Swanson traced the salmon industry from nineteenth-century canneries in the Pacific Northwest that processed local river-caught wild salmon, to Chilean “sea ranching” operations that hatch and grow Chinook salmon using the cold ocean currents that sweep up to South America from Antarctica, where Chinook salmon is a non-local species. Many salmon farming operations attempt to use discarded or unwanted parts of the fish’s bodies in feeding developing fish, echoing some of the cyclical metabolic processes that Landecker discussed. Swanson argued that tracing salmon reveals the ways in which entire landscapes, not just species, are domesticated in the service of raising massive numbers of animals.

The conference’s final discussion brought the participants together to focus on cross-cutting issues and outstanding questions. Participants noted the huge range of scales discussed over the course of the conference, from zoonotic disease to feral dynamics to fisheries to dairy farms to planetary health – all necessary for the radical approach needed to map and address global climate change and global health. Calling for continued discussions across disciplines and broad dissemination of findings, they also noted the many unanswered questions raised.

Jim Scott closed the conference, noting that while much of the conference focused on feeding the human population whose material consumption (especially in the developed countries) is growing even faster than their numbers. “We have, willy nilly, become the incompetent “zoo-keepers” of both the domesticated world and the “wild” world whose persistence depends on human action.” He asked: What are our ethical obligations to the world of domesticates whom we ‘created’? To the world of non-domesticates whose fate we also determine?

Thanks to the Brooks Institute for Animal Rights Law and Policy, the Brooks McCormick Jr. Trust for Animal Rights Law and Policy, and the MacMillan Center for financial support.