Interview with James C. Scott on the origins of the Independent Journal of Burmese Scholarship(IJBS)

James Scott, Ph.D., Yale University, 1967, is the Sterling Professor Emeritus of Political Science and Professor of Anthropology at Yale University. He is co-director of the Agrarian Studies Program. He specializes in research on political economy, comparative agrarian societies, theories of hegemony and resistance, peasant politics, revolution, Southeast Asia, theories of class relations and anarchism.

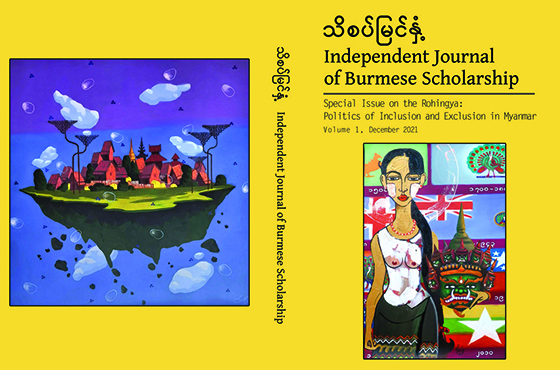

Professor Scott is the co-editor of the third and latest issue of the Independent Journal of Burmese Scholarship (IJBS). The IJBS is a bilingual publication in both English and Burmese which provides a forum for “publications that contribute to the knowledge of and in Myanmar.” Since the February 2021 military coup, the IJBS has moved its publishing operations outside of Myanmar to “continue to publish without fear or favor.” The Journal released its third issue, Special Issue on the Rohingya: Politics of Inclusion and Exclusion in Myanmar, in December 2021.

Tun Myint, Ph.D., 2005, Indiana University, Bloomington, co-edited the issue. Professor Myint is an Associate Professor of Political Science at Carleton College.

In this interview, Professor Scott discusses the origins of the IJBS, themes of past and future issues, and the Journal’s latest issue on the Rohingya.

Interviewer questions are bolded, with Professor Scott’s responses in plain text.

Interviewer: How did you first become interested in Burmese scholarship?

My interest in Burma began even before graduate school. Through a series of accidents, I ended up doing an honors’ thesis at Williams College on Burma and its economic development with the help of an economist. I was on my way to Harvard law school because I couldn’t figure out what to do.

As a lark I applied for a fellowship to go to Burma, and I got it. So, I decided that I could always go to Harvard Law later, but it was my chance to go to Burma. I spent a year there doing field work. That was my first serious experience abroad.

I fell in love with Burma—both in the traditional sense and in an intellectual one.

When I began graduate work at Yale, I wanted to study Burma and I did some papers on it, too. But Burma had closed in 1962 after the military takeover. I began my graduate work in 1961 at Yale, and by 1962 the country was closed to outsiders—its borders remained closed for the next 20 years or so. I didn’t want to do a dissertation on a country I couldn’t do field research in.

I ended up doing my dissertation on Malaysia and later spent a couple of years in a Malaysian village researching for another book called Weapons of the Weak.

My first love—work on Burma—was postponed for about 40 years. Although I did a lot of library research concerned with Burma, I couldn’t do any field work.

Starting in the 2000s, when the country opened up, I started to go back to Burma. Because the first time I went there was 40 years ago, I had lost the Burmese that I once knew in the interim. I started to hurl myself at Burmese language study. I’ve even given a talk in Burmese and written a 40-page summary in Burmese of my book, The Art of Not Being Governed. I would go to Burma regularly, and the rest is history.

After restarting your field work in and engagement with Burma, how did you come to start the Independent Journal of Burmese Scholarship (IJBS)?

I had been going to Burma every year for five or six years. One of the main sources of scholarship on Burma is the Burma Research Society, which was a colonial entity. You can find them all over the world in former British colonies. And French colonies, too, for that matter, as well as Dutch colonies.

The Society was started by colonial officials in 1905 who had an intellectual interest in linguistics, archaeology, history, etc. They would meet and give papers to one another; in 1911 this became the Journal of the Burma Research Society (JBRS). Gradually, Burmese members were included, and it became the premier journal for scholarship on Burma. It was closed by the military regime in 1979.

My idea was—why don’t we revive this journal? This became the Independent Journal of Burmese Scholarship (IJBS).

The original version, JBRS, was only in English. I thought we should revive it in Burmese and English and include minority languages as well. I got a small grant from the Council on Southeast Asian Studies (CSEAS) to bring together a bunch of scholars on Burma. Most of them were Burmese. Many were in the diaspora. From there, we hatched the idea of starting the IJBS. I got a grant for the Henry Luce Foundation for that.

Later, while I was in Burma, Aung San Suu Kyi came to Yale. Yale’s then-President Levin was mesmerized by her and asked, “What can I do?”

We asked for money for the journal, and he gave us $150 thousand toward it. That’s how we got our financial footing, and the project was underway.

Once you had the funding, how did you begin putting together the issues?

Once you had the funding, how did you begin putting together the issues?

We tried to work without a formal editor for several years. The idea was that it would be like a training procedure—we would find a theme for each issue. This was quite different from the old issue. For each issue or theme, we would convene a workshop of people who seemed to know most about that topic. Contributors would present papers. Their papers would be questioned, they may be revised, and so on.

Whoever had convened the workshop would be the editor, and then we would publish the journal.

The third and latest issue of the IJBS is on the Rohingya. What was the subject matter of the earlier two issues?

We published the first issue of the IJBS in 2016, a special issue on poverty. The editor of the issue was a woman named Ardeth Thawnghmung. She trained at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and did a wonderful collection on poverty in Rangoon and how families cope with the problems of everyday subsistence. She’s now at the University of Massachusetts Lowell.

The second issue was initiated by a Danish woman, Helene Maria Kyed, who pulled together a bunch of young Burmese scholars to study what she called “everyday justice” in Myanmar. We published this online in 2018 and in print in 2020. The theme of that issue was how people resolved conflicts over land, etc., without bringing in the government. We asked: what were the indigenous forms of dispute settlement and how did they work?

Our third issue, published in December 2021, focuses on the politics of inclusion and exclusion in Burma—specifically in the case of the Rohingya.

And there are two other issues that are just about in the final stages. One is on Burmese feminism, and another—which has been stalled in the wake of the February 2021 military coup—is on public memory.

Another issue in the works is about defectors from the Burmese military.

Could you share more on how the latest issue on the Rohingya came together? I imagine such a politically fraught topic may have presented challenges to the contributors and advisory committee.

The workshop on the Rohingya we convened was a topic of a tremendous amount of conflict. Many Burmese with whom I previously stood in agreement on other issues either took the position that the issue was not of their concern or that the Rohingya were not citizens of Burma. Then there are those who simply wanted to ignore the persecution of the Rohingya and claim that what we say happened had not.

I took the position that Aung San Suu Kyi was grossly negligent in ignoring the abuses of the Rohingya and that, regardless of their citizenship status, they should be afforded basic human rights protections guaranteed by the United Nations. After all, Burma is a signatory to the UN.

In any case, we couldn’t hold this workshop in Rangoon because we thought that the people who attended it may have gotten threats, or that it may have been broken up. We held it in Chiang Mai, Thailand.

The latest issue was published in Chiang Mai. Our journal is, at this point, in a sort of exile to Thailand.

And what would you hope readers take from this issue on the Rohingya?

This issue is a collection of several papers related to issues of citizenship, religious tolerance, and the treatment of the Rohingya. It aims to offer diverse perspectives on how and whether Burma may one day achieve its stated goal of being inclusive to the many ethnic and religious groups that reside in its borders.

One paper, for example, looks at the rise of Islamophobia on social platforms like Facebook. Another examines the politics of citizenship in Burma—that is, who is considered a citizen and how this relates to the treatment of groups like the Rohingya.

Generally, I would hope readers find a deeper and more nuanced understanding of the Rohingya crisis by reading this issue.