New data on India's migrant workers and Covid-19

Economic Growth Center and MacMillan Center researchers, along with collaborating researchers, have conducted large-scale surveys of migrant workers in India. The findings can inform the policy response to the current outbreak.

Over a Year after the First Covid-19 Lockdown, Migrants Remain Vulnerable

A ferocious second wave of coronavirus infections has hit India, prompting a new round of localized lockdowns. Last year’s restrictions devastated the lives and livelihoods of poor migrant workers, leading to widespread job loss, mass re-migration, and social safety nets unable to support the most vulnerable. Policymakers have signaled their intent to minimize the economic effects on migrants through better targeted, less restrictive lockdowns and two months of free food for poor households. This is encouraging, but additional longer-term measures are needed. Many who migrated home last year continue to struggle and those who had returned to cities were only just beginning to make up for economic losses.

Since April 2020, we have tracked a group of roughly 5,000 migrants who returned to their home villages in central and northern India following the nationwide lockdown in March.

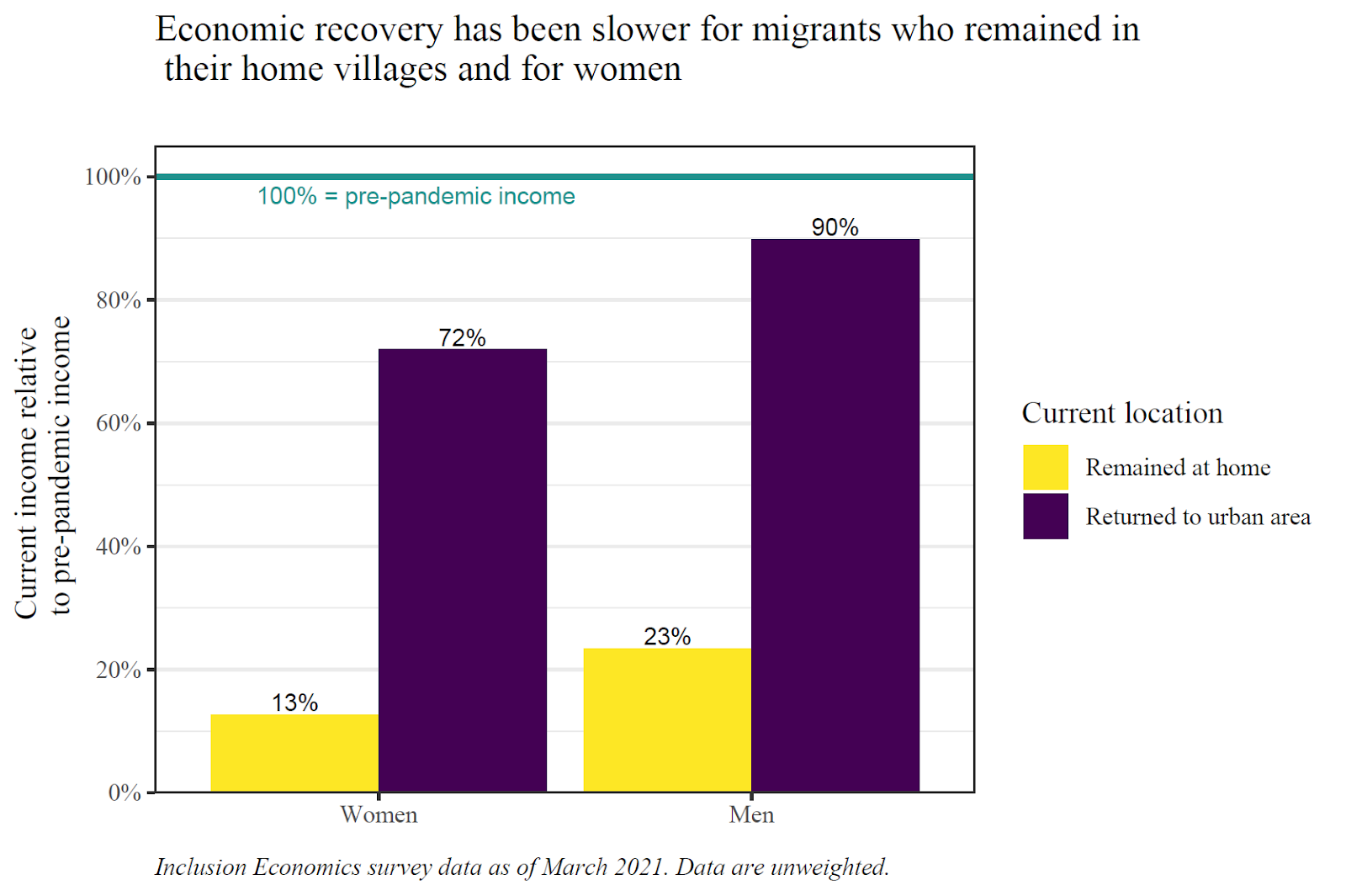

By February 2021, slightly more than half the sample had remigrated, with economic recovery differing dramatically between these remigrants and those who remained in rural areas. Remigrants reported weekly earnings of Rs. 2400 ($32.16, 85% of their pre-pandemic income) while those who remained at home earned roughly a fifth of that amount at Rs. 450 ($6.03) a week (18% of their pre-pandemic income). Those who remained at home in rural areas were more likely to report being unemployed, reducing food consumption, mortgaging or selling assets, spending down savings, and taking loans to make ends meet. To the extent it is possible to help those who returned to urban areas remain in cities through localized lockdowns, such as by providing economic support through employers and rations, we can protect migrants from another costly return to rural areas and enable a speedier economic recovery.

Heading home remains for many a last resort – the evidence on those who stayed home after the lockdowns shows continued food insecurity. In August 2020, a majority were concerned they would run out of food, and over 30% reported eating less than they usually would. By February 2021 – after bumper harvests that should have supported recovery – 41% were still concerned that they would run out of food, and over 21% were still eating less than they normally would. It is also likely that food rations will be needed for more than two months. Our surveys show that food insecurity remained higher over the months following the nationwide lockdown among those not able to access rations: almost 29% percent of those receiving rations reported eating less than usual in the past week in August 2020, compared to 39% percent of those who did not receive rations.

Lastly, in rural areas, policy efforts should maintain a deliberate focus on women. Almost a full year after the pandemic, only 47% of women had re-migrated, in contrast to 55% of men. The gender unemployment gap was even starker, with only 59% of women having earned income in the past seven days, compared to 74% of men. In the coming months, a recommitment to providing rural-based employment will be a critical lifeline for those who must remain in rural areas.

India has accomplished and learned much since the massive disruptions in early 2020; right now, the health needs in city hospitals are immediate. But our data suggest that economically vulnerable informal sector workers – in both urban and rural areas – will also need sustained support. While aggressive localized containment measures are necessary to prevent the health infrastructure from being further overwhelmed, the economic effects will surely outlast the second wave. Providing urban employers resources to ensure workers have a short-run safety net and increasing the capacity and responsiveness of existing social safety net programs – including PDS, MGNREGA, and programs linking the poor to jobs – over the longer term will be essential for ensuring that migrants can get back on their feet again.

This research is based on surveys implemented by, and related support from, Inclusion Economics India Centre at KREA University. Cover image: Migrants wait in queues to receive food being distributed by the volunteers outside the Railway Station during in Guwahti, Assam, 4 June, 2020.

Suggested citation

Inclusion Economics, 27 April 2021. “Over a Year after the First Covid-19 Lockdown, Migrants Remain Vulnerable.” New Haven: Economic Growth Center.

Written by Jenna Allard, Nils Enevoldsen, Maulik Jagnani, Charity Troyer Moore, Yusuf Neggers, Rohini Pande, and Simone Schaner

Read coverage of this research in The Indian Express

“Study: Migrants who returned earned five-fold of those who stayed back” by Karishma Mehrotra, 28 April 2021