Students Abroad: Edward Columbia in Mangang Village, PRC

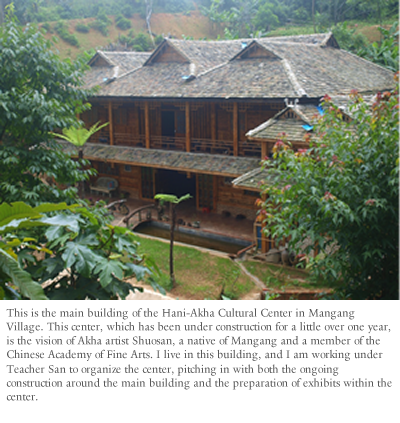

With funding from Tristan Perlroth Prize for Summer Foreign Travel, Edward Columbia, a Class of 2018 history major, traveled to Mangang Village, Xishuangbanna, Yunnan Province, PRC, and is working at the Hani-Akha Cultural Center in the jungle. He’s shared one of his daily journal entries with the MacMillan Center that highlight some of his experiences in the village.

June 8. Today was a rest day from the heavy work. Since June 5 I had been helping to move brick, lumber, and bamboo to clear work sites around Teacher San’s cultural center, tidying up the place in preparation for the grand opening to come at the end of this month or early next. The cultural center that Teacher San is developing in his home village of Mangang, high up in the mountains of Xishuangbanna, is devoted to the artistic lifestyle traditions of his people, the Akha, and of the broader Hani ethnic group. I am here for one month to serve as Teacher San’s assistant, a role that covers any number of tasks, from piling big bamboo to writing English translations for the center’s exhibits, from teaching conversational English to San and the young Akha people working here to sweeping the floor and preparing breakfast.

This morning I woke up just after Teacher San did, and went outside to find him standing over the fish pond that stretches the length of the building’s front. It was running very low, many of the fish swimming sideways to stay submerged in the water, or gathering in the two deep holes at either end. It took some time before Teacher San and a man from the village figured out where the break was in the aqueduct and got water flowing to the fish again. While they worked on this, I made oatmeal for us with powdered milk.

This morning I woke up just after Teacher San did, and went outside to find him standing over the fish pond that stretches the length of the building’s front. It was running very low, many of the fish swimming sideways to stay submerged in the water, or gathering in the two deep holes at either end. It took some time before Teacher San and a man from the village figured out where the break was in the aqueduct and got water flowing to the fish again. While they worked on this, I made oatmeal for us with powdered milk.

Teacher San was expecting several guests at the center, so my first duty in the morning was to sweep the entire ground level, inside and out. My sweeping skills are improving, but occasionally Teacher San would walk by and grab the broom and dustpan from me to demonstrate the proper technique. Especially interesting was when I would come to a new room and, before I had begun sweeping, Teacher San would shuffle in, comment on how dirty the floor was, and ask whether I had never swept a floor in my life.

After sweeping I thought I would make myself useful by cleaning the previous day’s dirty dishes, which had piled up in the sink from lunch and dinner and become rancid overnight. I added our breakfast bowls and set to it all with a soapy rag. I soon noticed that under a dirty lid in one sink was a smelly plastic bag. I figured it contained the river fish heads from the last lunch and tipped it into the sink to see. The bag was full of live eels and fish. These were now swimming in the dirty dish water of the clogged sink, among the oats from breakfast.

After sweeping I thought I would make myself useful by cleaning the previous day’s dirty dishes, which had piled up in the sink from lunch and dinner and become rancid overnight. I added our breakfast bowls and set to it all with a soapy rag. I soon noticed that under a dirty lid in one sink was a smelly plastic bag. I figured it contained the river fish heads from the last lunch and tipped it into the sink to see. The bag was full of live eels and fish. These were now swimming in the dirty dish water of the clogged sink, among the oats from breakfast.

Have you ever tried catching eels and fish in a sink? I suspect it is on the order of shooting them in a barrel. Not as difficult as doing so in a river, but no where near as easy as people would have you think. I put on gloves and for the next half hour had my hands full snatching them out of the sink and putting them back into the plastic bag a quarter full of water. Occasionally I would have an eel out of the sink and on its way to the bag, only to lose its wriggling body through my fingers. I would then chase it around the kitchen counter. Sometimes, in the murky water, I would think I had one gripped tight, only to find that no, that was a spoon. Eventually I drained the dish water, rendering the slippery creatures a little helpless and out of breath. Still, I had to steady my hand to avoid pulling it back from reflex every time they jerked violently at my touch.

After the eel and fish fiasco, I finished the rest of the dishes and went to see what more I could do to help Teacher San prepare for visitors. Nothing immediately, so I set about writing a very long letter that I will mail from the post office in Jinghong on a prayer. Not long after I had sat down to write–I was halfway through describing my misadventure with the eels–Teacher San called my name. He often half-shouts, half-sings my name repeatedly from out of sight, and I only discover where he is by following the sound of his voice.

I found Teacher San outside the kitchen, holding two uprooted Japanese banana trees, very small ones, dirt still clinging to their fibrous bottoms.

I found Teacher San outside the kitchen, holding two uprooted Japanese banana trees, very small ones, dirt still clinging to their fibrous bottoms.

“Let’s plant these,” he said. “They will be very beautiful when they flower.”

“Great, where would you like to plant them?” I asked.

“You grab a hoe and figure it out.”

“Ok.”

I took a hoe from the back of the guest house, and we decided on a patch of dirt between the two buildings.

“Do you know how to till?” he asked.

“Sure,” I said. (meaning, I know that the instant I hit the ground you will tell me that I have no idea how to till earth, but hey I’ll give it a shot.)

I began digging up the dirt with the hoe. Sure enough, after a few swings he shook his head and grabbed the farming tool. Teacher San handed me the sapling and began striking ferociously at the ground, wrenching it up and pulling rocks away with the hoe until he had dug a small hole. I placed the tree in and held it in place while filling in the dirt.

Once we had planted both trees, we sat for a while drinking tea in front of the main building. Teacher San swung gently in his onion bulb chair, and I took a seat on the tree-skin covering the wicker bench. I can’t figure out why, but that particular seat is the most attractive to flies of anywhere on the place. I don’t mind them. I am so covered in bug bites of every shape and size that a few house flies are welcome.

I boiled the water for tea, and Teacher San brought out a bag of dark black leaves– high quality red tea, he explained, that a friend had brought him from nearby Myanmar. I have never seen such a color. By the third round of water, it had reached an amber so rich that you would expect to find an ancient insect preserved inside of it.

I boiled the water for tea, and Teacher San brought out a bag of dark black leaves– high quality red tea, he explained, that a friend had brought him from nearby Myanmar. I have never seen such a color. By the third round of water, it had reached an amber so rich that you would expect to find an ancient insect preserved inside of it.

Soon the first car arrived– an old friend of Teacher San’s named Uncle Sun, and a friend he had brought along named Uncle Bao. I went to greet them as Uncle Sun came up the muddy driveway laden with bags of gifts for Teacher San. He had brought with him a lovely ceramic tea set and several bottles of red wine from Xinjiang, where he is originally from. Uncle Sun left Xinjiang when he was eighteen and has lived in Jinghong, where he has a wife and kids, for over ten years. It turned out that he had also brought with him a device specially designed for brewing red tea, which we tried out on the leaves from Myanmar.

Teacher San busied himself tidying up the ground around the small guest house while I sat with Uncle Sun and Uncle Bao. The latter man was one of very few words. Mostly he sat smoking cigarettes. Uncle Sun and I talked about Xinjiang, which he compared geographically and topographically to Texas. We discussed different independence movements, not only in Xinjiang but elsewhere. He was skeptical of what would ensue should any such independence movement actually be successful, but we came around to the concept that struggles for independence were primarily struggles for basic rights.

We spoke also about the depth and breadth of Chinese history. Thousands of years of history and culture, in Uncle Sun’s view, carry with them remarkable advantages and extraordinary disadvantages. He marveled at the ability of younger nations to start anew, to choose more freely from a range of options available–be it in means of government, systems of law, modes of technology, etc. To Uncle Sun, China’s five thousand years of history are as constraining as they are rich.

We spoke also about the depth and breadth of Chinese history. Thousands of years of history and culture, in Uncle Sun’s view, carry with them remarkable advantages and extraordinary disadvantages. He marveled at the ability of younger nations to start anew, to choose more freely from a range of options available–be it in means of government, systems of law, modes of technology, etc. To Uncle Sun, China’s five thousand years of history are as constraining as they are rich.

As we were talking, Gaotu arrived with the other guests– a couple from Hubei who had flown into Jinghong from Wuhan that morning. They came up the driveway laden with bags of fresh vegetables, fruit, and other deliciousness.

Shuosan showed the guests around the cultural center, and I pitched in where I could but mostly stayed scarce, writing.

Gaotu outdid himself preparing a spectacular lunch, which all came together to enjoy.

After we all ate, Gaotu begged his leave. He works for the government as an engineer in Mengla, around four hours’ drive away. Work keeps him busy, but he visits his mother in Mangang as often as he can manage. Three years ago, both his mother and father took ill, and his father passed away. Gaotu was still in university in Shandong at the time. Teacher San regards him very highly– a hardworking man and dedicated son to be proud of.

After we all ate, Gaotu begged his leave. He works for the government as an engineer in Mengla, around four hours’ drive away. Work keeps him busy, but he visits his mother in Mangang as often as he can manage. Three years ago, both his mother and father took ill, and his father passed away. Gaotu was still in university in Shandong at the time. Teacher San regards him very highly– a hardworking man and dedicated son to be proud of.

I was sad to see Gaotu go. We had gotten along very well. Often while he was working in the kitchen, I would keep him company and go through some practical English, which he was keen on learning. He called me his ‘slang teacher.’

“The English we learn in school isn’t all that useful,” Gaotu said. “Too formal, and I’ve forgotten most of it.”

“Well, even from Mengla, you can always ask me anything with WeChat.”

“Will do, and hopefully we’ll meet again before you leave. If you have time, come to Mengla and hang out.”

“Of course!”

After Gaotu departed, Teacher San, Uncle Sun, Uncle Bao, the man from Wuhan, and I grabbed a few machetes and baskets and set off into the jungle for a long outing of vegetable and leaf picking. Teacher San led the way as we followed the stream up the mountainside, occasionally detouring off of the path to patches of vegetables that he knew of. When we reached the small reservoir in the woods into which and from which the stream flows, we cut through the trees to rejoin the mountain path.

After Gaotu departed, Teacher San, Uncle Sun, Uncle Bao, the man from Wuhan, and I grabbed a few machetes and baskets and set off into the jungle for a long outing of vegetable and leaf picking. Teacher San led the way as we followed the stream up the mountainside, occasionally detouring off of the path to patches of vegetables that he knew of. When we reached the small reservoir in the woods into which and from which the stream flows, we cut through the trees to rejoin the mountain path.

Teacher San still recalls taking this path down the mountain in 1968, when he was only four years old. His entire village moved from the mountaintop to what is now Mangang. They burned the old village behind them. A very young Shuosan carried a basket of four whelping puppies on his back. He remembers his younger brother crying on his mother’s back, and his older brother, six at the time, crying as well under a heavier load.

We paused on the mountain road as Teacher San recounted this story. He told us that he could remember when he was even younger, perhaps one or two, bouncing on his mother’s back as she went to fetch water from the mountaintop spring. Many foxes would gather around the water. The Akha believe that foxes are the pet dogs of ghosts. Teacher San remembers how his mother would call out to shoo them away.

I would often let the group get ahead of me. Pause, close my eyes on the path. The stillness. Jungle is smaller than sea and bigger than imagination.

On the way back I wandered into an abandoned tea factory on the ridge above the cultural center. Before closing some six or seven years ago, this had been the primary processing area for Mangang’s famous tea.

We returned to the center, and I finished writing my long letter. I was restless to return to the forest.

We returned to the center, and I finished writing my long letter. I was restless to return to the forest.

“Do you dare to go by yourself?” Teacher San asked.

“Yes.”

“Very well. Be back before the big rain.”

I set off up the mountain path, making a point of remembering where and how I turned. After walking some distance I stopped and stared through the big bamboo out at the flatlands, the mountains green beyond them. I breathed very deeply at this time, and my breathing was good. I took the stillness into me, inside. I was empty. There was nothing in my mind. The wind came to my back. The rain behind it.

A little further down the road, I came upon an old man with a craggy face and a rifle. At his feet were a burlap sack and a machete. I sat with him a while.

A little further down the road, I came upon an old man with a craggy face and a rifle. At his feet were a burlap sack and a machete. I sat with him a while.

Grandfather told me that he was there hunting squirrels. He opened the sack and pulled out a squirrel that he had shot in the eye. There were a couple of drops of blood on the leaves where I squatted. I took a cigarette from him and lit his, then mine, to be polite. It soon went out, so I tucked it behind one ear. I enjoyed our exchange and the long pauses in the midst of the words.

“They haven’t come out yet,” he said.

“Do you wait until it begins to rain?”

“No, wait until the light is dimmer. They won’t come out when it’s bright.”

“But how do you see them in the dark?”

……….

“You here alone?” he asked.

“Yes.”

“Only you.”

“Yes, only me.”

“How long have you come for?”

“One month.”

“One month!”

“Yes, I’m staying at Shuosan’s Cultural Center. I’m trying to help with his projects. I’m working for him.”

He laughed.

……….

“Grandfather, do you remember when you moved as a village from the top of this mountain to where you are now?”

“I was seven at that time.”

“Only seven years old!”

“Ay, only seven years old. Now I am sixty-two.”

“Wow.”

“At that time there was also a road here that led to a school in the forest. When I was seven I was going there to study.”

“Your school was in this forest?”

“Yes, in the mountain forest.”

“Teacher San mentioned that. He said the first time he ever went to school, it was to attend that school in this forest.”

“That’s right. We had two teachers, a man and a woman.”

“Were they Han?”

“Yes, they were Han people.”

……….

“Your rifle is very old.”

“I made it myself.”

“You made it yourself?”

“Yes, I made it myself.”

He handed me the rifle. I looked through the sight.

“It is very heavy.”

“Yes. You can’t use it to hunt anything bigger than a squirrel, though.”

……….

“The squirrels are not coming out.”

“The squirrels are not coming out.”

“Oh no?”

“Not so good, to have bagged only one.”

Grandfather gathered his bag, his knife, and his gun. He stood.

“I will go back to the village. I have to buy some oil.”

“All right.”

“Don’t be long coming back. If you follow this road, it will take you to the top and back to the village.”

“The same road?”

“One road.”

“Goodbye now,” the old man said.

“Goodbye.”

I watched him walk.