Was Columbus’ Voyage to the “New World” Driven by Islamophobia?

Popular views of the explorer see him as intrepid adventurer or bungling murderer. But he was also a religious crusader.

The following interview with Alan Mikhail, Professor of History, appeared in Slate on October 12:

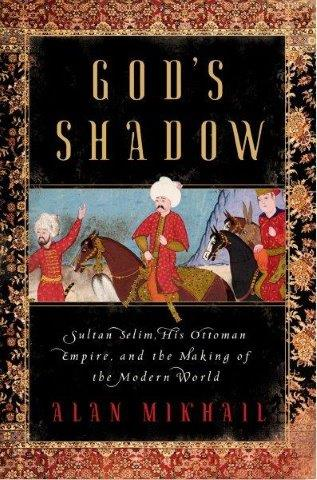

Tucked inside historian Alan Mikhail’s new biography of Sultan Selim, the ambitious early-16th-century ruler of the Ottoman Empire, is a riveting series of chapters about Christopher Columbus. Mikhail’s ambition in writing God’s Shadow: Sultan Selim, His Ottoman Empire, and the Making of the Modern World was to restore the place of the Ottoman Empire in the global history of the early modern period. To that end, the Columbus chapters make the argument that at its inception, European exploration of the New World can be understood as an ideological extension of the Crusades—a new effort to circumvent the ever-more-powerful Islamic presence in Europe.

Because this argument is somewhat hidden inside a big biography of an Ottoman ruler, it’s not been as controversial with traditionalists as the 1619 Project’s recasting of American history around slavery, but it’s got a similar power to make you look at a major historical happening in a completely new way. I asked Mikhail to explain how Columbus came to commit himself to combating Islam, how his feelings about Muslims affected his approach to the New World, and whether the Europeans of this time could rightly be called “Islamophobic.”

This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Rebecca Onion: There are a few common popular stories of Columbus. The first one is the elementary school version, where a brave explorer sets out for strange worlds—basically, a hagiographic take. Then there’s the revisionist one: Columbus was a blunderer who didn’t know what he was doing and just kind of happened onto the “New World.” But this is another twist, what you’re writing about.

Alan Mikhail: Yes, and of course there are also corollaries of the two versions of Columbus you talked about: the Italian American hero and the genocidal murderer.

Oh! Of course, I assumed the “genocidal murderer” part was understood, but thank you for making that clear.

Ha, yes. What I’m hoping to do is to point out something else that’s crucial to his biography, and that’s right there in his own writings and in the understanding of his age: He was a crusader.

olumbus was born in 1451 in Genoa—a really important mercantile port city but also a crusader port city. He was born two years before the Ottomans captured Constantinople, in 1453. And that was seen as an apocalyptical loss for Christian Europe. The Ottomans had—in the words of one of the Popes—“plucked out one of the two eyes of Christendom,” which were Rome and Constantinople, the Eastern capital.

In very real terms for a place like Genoa, this made a difference, because Constantinople, through the Bosphorus strait, had provided access to the eastern Black Sea; that is where Genoa had many of its trading ports, to connect to places further East. So there was this sense of loss in Genoa that was religious but also economic.

Genoa also had lots of crusaders going in and out of its port, when Columbus was young. We think of the Crusades as only happening in the medieval period, in the 11th and 12th centuries, but there were calls for Crusades up through the 17th century. To various degrees of effectiveness, of course. But Columbus was alive when there were crusaders going in and out of his city, and one of the crusading orders had a hospital in Genoa.

So Columbus was brought up on this story of loss. And he also read works like Marco Polo’s. One of the things that would become very important for Columbus, that he took from reading Marco Polo, is the idea of the “Grand Khan.” This is a person Polo wrote about that maybe has some connection to various actual historical figures. He’s supposed to be a ruler in a far-off place in Asia, who Polo says has shown interest in converting to Christianity. If this “Grand Khan” would convert, Polo’s readers were thinking, he would bring his subjects along with him, and there’d be this big Christian ally way off in Asia that would let Christians surround the Muslims in the Middle East and basically crush them.

That idea was very important to Columbus. On the first page of his logbook recording his voyage, Columbus writes to Isabella and Ferdinand, the Spanish sovereigns, that they had sent Columbus on a mission to India to find the Grand Khan. He’s very explicit about this being a reason for the trip.

These were ideas he absorbed when he was young, but he had personal experience encountering Muslims, too, before he set off on the voyage.

Yes, when he finally set to the sea as a teenager, in his early ventures as a sailor for hire, a couple of voyages took him to various parts of the Muslim world. He was hired by the king of Anjou in France to retrieve a ship of his that had been captured by pirates based in Tunis, on the North African coast. That was the first time that Columbus was face to face with a living, breathing Islam—not the kind of fantasy he had read about or heard about in Genoa. We don’t know the outcome of that voyage—he probably didn’t retrieve the ship—but that’s the first time he encountered the Muslim world in any kind of way.

There was another voyage that took him to Chios, an island off the Anatolian Coast in the Aegean Sea, and there he met Greek soldiers who had fought in defense of Constantinople. So he heard these real-life stories about this loss of a Christian city to this Muslim power. He sailed with Portuguese navigators down the West Coast of Africa, and there again, encountered Muslim powers. He got this sense that, even once you sail out of the Mediterranean, and are in this very different kind of place, West Africa—Islam is going to be there to greet you.

Then he was present at the siege of Granada in 1492, when Isabella and Ferdinand captured Granada. And in that logbook I spoke about, he connects that event—the expulsion of the last Muslim ruler from Spain—with the sovereigns’ decision to send him on the voyage, to find a new route to Asia and to connect with the Grand Khan. To him, these things were all tied together.

And this worked with Isabella and Ferdinand in part because of the politics of European rulership. They controlled property in Italy, specifically Sicily, that the Ottomans, or so they thought, were poised to invade, at various points. And of course, there were still many Muslims in Spain after the conquest of Granada; the sovereigns saw those Muslims that remained as a potential fifth column—internal enemies, maybe allies to the Ottoman Empire, the Mamluks, or Muslim powers in North Africa.

They sort of felt like Islam was breathing down their necks.

There are a lot of examples of the ways Columbus and other explorers approached the Native people in the New World, primed to perceive them in the same way they thought of the Muslims they had encountered in Europe.

This is the other half of the story, which is that the explorers used language around Islam to frame their experience of the Old World, once they got to the New World. Some examples: Columbus described the weapons of the Taíno—the Indigenous people of the Caribbean—as alfanjes, which was the Spanish name for the scimitars used by Muslim soldiers. Hernán Cortés said that there were 400 “mosques” in Mexico, by which he probably meant Aztec temples, and that Aztec women look like “Moorish women.” He describes Montezuma, the Aztec leader, as a “sultan.” This first generation of conquistadors were forged in this world of warfare between Islam and Christendom, and that’s what they thought of in their minds’ eye, when they thought of enemies.

And they also thought maybe they were seeing these signs of Islam because they were in Asia, where it would make sense, right?

Yes, well, it depends on who you’re talking about; Columbus, until the day he died in 1506, thought he’d landed in Asia. So he thought all he needed to do was find the right path in, to the Grand Khan. But even much later, way beyond Columbus’ time, in the 1580s or something, when it was clear the Americas weren’t Asia, the Spanish authorities in what is today Peru reported rumors that Ottoman ships were off the West Coast of South America. There’s zero historical evidence so far that this was true—I mean, I’m open to change my mind if somebody finds evidence!—but what I’m interested in is this idea they still seemed to have that Islam is everywhere; Muslims are all around us.

Is it possible to use the word Islamophobia to describe the way Columbus, Isabella, Ferdinand, and other Christian Europeans felt at this time? I don’t know if that’s ahistorical. What was the motivation for their animus? Anxiety about territory? Religious fear?

I didn’t use the word Islamophobia in the book. That’s a very modern term; I would be hesitant to apply it to this period. Maybe something like “anti-Muslim sentiment,” which, to be fair, is clunkier.

It’s very tricky, the answer to this question. The idea is that there’s a thread of anti-Muslim sentiment from this period, and maybe even before, to today. In some ways you can draw a throughline. But I don’t want to buy into a story about some kind of eternal “clash of civilizations,” because there are plenty of examples of Christian Europeans and Muslims having quite positive interactions at the same time I’m talking about: the sharing of ideas, the exchange of goods, diplomatic relationships, fighting on the same side of wars against other enemies. And that’s part of the book, too—to point out that the Ottoman Empire has been part of “our history.”

Why do you think it was important to highlight this angle on Columbus’ story?

As I started writing this as an epic history, curious about the Western perspective on this, I thought, Why isn’t this motivation—this crusading motivation—part of the Columbus story? I mean, if you go back to Columbus and the Spanish sovereigns we are talking about, who wanted to deny and defeat Islam, they succeeded, in that the narratives about the New World do exclude Muslims. That’s part of the legacy.

If you think of the imports, if that’s what you want to call them, that Columbus brought with him in 1492, you have disease, an ambition to find Asia, and a crusading spirit of anti-Muslim sentiment. And very tragically, to write this history of what happened next, you then have to fold what happened to the Native people of the Americas into Europe’s anti-Islamic history.

And again, I don’t want to get too transhistorical here, but there are some ways in the modern American psyche that there are still connections between Muslims and Native Americans. You see that today, in the way the main American theater of warfare is the Muslim world, and so much American weaponry used there is named after Native Americans—Apache helicopters, Black Hawk helicopters, Tomahawk missiles. There’s a history of American warfare with Native peoples that’s playing out again, in different ways in the Muslim world.

You could say, Those are just names, it’s language, that doesn’t mean anything. But it does! There are reasons why discursive echoes like these exist. There’s a reason that Columbus and Cortés used language referring to Islam, when they encountered the New World, and not the language of anti-Judaism. They didn’t talk about, I don’t know, “the dirty French,” or something like that. There are particular reasons for that, that have to be explained.

For more information about Professor Mikhail, visit his website.