Writing/Curating the Middle East

The cultural production of the Arab World and Iran is often viewed through the limiting lens of European and American modes of art theory. “Writing/Curating the Middle East”—a two-day symposium (March 30–31) sponsored by the History of Art Department, Yale University Art Gallery, and Council on Middle East Studies at the MacMillan Center—sought to challenge this historiographical limitation. Examining issues of national identity and diversity through historical entanglement and synchronicity, curators and art historians proposed a new discourse on art from the Middle East.

Consisting of an artist talk and three thematic panels, the symposium illustrated the region’s ties to global modern art movements. Speakers included Wael Shawky, University of Pennsylvania; Linda Komaroff, Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA); Sultan Al Qassemi, Barjeel Art Foundation; Alex Seggerman, Smith College; Clare Davies, Metropolitan Museum of Art; Dina Ramadan, Bard College; Saleem Al-Bahloly, Johns Hopkins University; and miriam cooke, Duke University. Kishwar Rizvi, Co-organizer and Associate Professor of Islamic Art and Architecture,Yale University, introduced the symposium, with a roundtable discussion led by Pamela Franks, Co-organizer and Senior Deputy Director, Seymour H. Knox, Jr., Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, Yale University Art Gallery. Individual panels were moderated by Frauke V. Josenhans, Horace W. Goldsmith Assistant Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, Yale University Art Gallery; Mandy Merzaban, Curator, Barjeel Art Foundation; and Najwa Mayer, Wurtele Gallery Teacher, Yale University Art Gallery.

The symposium began, Thursday night, with the display and discussion of Wael Shawky’s Cabaret Crusades: The Horror Show File. Shawky and Rizvi considered the artist’s process and usage of historical “interlocutors” to narrate an Arab perspective of the Crusades. Shawky described the Crusades as “a dream for certain people to evolve,” a dream of development held in his memory of modern Alexandria: “I was fascinated by the idea of society in transition.” Humanoid porcelain and glass marionettes employed as actors served, Rizvi pointed out, to subvert expectations of race or type. Shawky explained that the shift from an orthographic, “specifically European vantage” in the first video to a frontal composite of maps, calligraphic text, and painted imagery in the final sequence proffers, if subtly, the import of perspective in historical memory. Both artist and art historian acknowledged the global production and chronological specificity of the Cabaret Crusades. “Ultimately,” Wael pronounced, “the work represents a decision to study and exhume history.” Viewed asynchronously as clips within the museum space, Shawky presents an endless history, with no definitive beginning or end, ripe for revisitation.

Opening Friday’s first panel, Collecting and Curating, Linda Komaroff presented a curatorial corollary to Shawky’s work. In “Contextualizing Contemporary Middle East Art within an Historical Collection,” she shared her experience merging contemporary acquisitions with the (early modern) Middle Eastern collection at LACMA: “Contemporary works signal virtuosity and connectivity, exciting and engaging an audience.” For visitors, “contemporary works,” like Mona Hatoum’s video-piece Measure of Distance, “create new expectations in the medieval Islamic gallery.” Works which are both “universal and highly specific,” allow “visitors to transcend the fear, difference, and xenophobia that sometimes separate us.”

Sultan Al Qassemi’s presentation on the “Politics of Modern Art,” encompassed a broad span of artists from the Middle East who reacted to political events in and beyond their respective nations, beginning with the Art and Liberty Group, whose periodical, Evolution, would famously proclaim “long live degenerate art!” “The group,” Al Qassemi emphasized, “was a political movement of artists, alongside lawyers, and professors.” The emergence of artist societies “played a critical role in the emergence of identity and the political arts of these countries.” Here, political art includes both state propaganda and subversive works, such as El Gazzar’s Popular Chorus—the canvas that resulted in the artist’s imprisonment.

Discussing the role of museums in facilitating the display of modern art of the Middle East and the division of such art within the museum space, both Komaroff and Al Qassemi agreed that the divide between the historical and the contemporary leaves modern art increasingly at stake. Al Qassemi further highlighted the issue of visibility: “We must allow Middle Eastern work to be shown throughout the region itself and not only within the U.S. and Europe.”

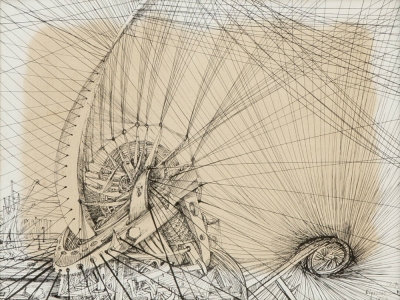

Beginning the panel on Art and History, Alex Seggerman discussed the evolution of Abdel Hadi el-Gazzar’s oeuvre in her paper “Mystical Men and Magic Machines: Abdel Hadi el-Gazzar’s Technology of Enchantment.” Employing Alfred Gell’s definition of enchantment, Seggerman related el-Gazzar’s earlier images of the mystical, urban, lower-classes to his fantastical drawings of modern machines (Fig. 1). While his later drawings obtain a certain linear rigidity, Seggerman expounded thematic parallels as “mystical beliefs and technological prowess express similar enchantments.”

Clare Davies’ ensuing talk, “The Figuration-Abstraction Continuum, and the Case of “Oriental” Artist Hamed Abdalla (1917-1985),” presented the central question: “What are the stakes of being a figurative artist in post-colonial Egypt?” Analyzing several of Abdalla’s paintings of women formed through and beneath calligraphic script, Davies suggested Abdalla’s central concern as reimagining the relation between abstraction and figuration. Drawing support from the artist’s written references to El Greco and the pseudo-scripts of Giotto, Abdalla’s oeuvre demonstrates an interest in reading before comprehension, emphasizing a “gap between a fallen present and a sacred past—dead, foreign, otherworldly.” The conflation of figure and text, of reading and looking, became a challenge to viewing modernity as a binary mapped onto the terrain of figurative or abstract art production.

Davies and Seggerman described the importance of writing and calligraphy in both artists’ works, as the pseudo-script of Abdalla provided a counterpart to the quasi-illegible machines of el-Gazzar. Both, too, emphasized the phenomenon of a global surrealism. “Surrealism is not a European invention,” Davies maintained. “One of the major issues is overlooking the complexities, densities, and richness between different artists within the Egyptian milieu as many of these artists attempted to elide their priors”—an historical elision which continued research seeks to ameliorate.

The final panel, Practice and Protest, opened with Dina Ramadan’s “The Science of Art: Knowledge Production and Artistic Practices in Early 20th Century Egypt.” Ramadan examined the notion of a division between art and science, with the possibility of multivalent fields of knowledge present in definitions of ‘Abduh’s 1904 fatwa, “al-Suwar wa-l-Tamathil wa-Fawa ’iduha wa-Hukmuha” (“Images, Statues, and Their Benefits and Legality”) and Muhammad Husayn Haykal’s later article, “al-Fann wal Fanan.” The preservation of art, as well as the comparison between poetry and art, fell under scrutiny. In Haykal’s definition of art as capturing “a truth that pre-exists and exceeds its maker,” Ramadan suggests “we can hear echoes of ‘Abduh’s concerns about the documentary potential of the visual and the pictorial.”

Following Ramadan, Saleem Al-Bahloly’s talk “The Resurrection of Tradition, or A Critical Theory of the Artwork in the Postcolonial World” explored the rhetorical function of mourning demonstrated in Kadhim Hayder’s series, The Epic of the Martyr (Fig. 2). Al-Bahloly spoke of the artist’s ritual imagery, namely his evocative horses, as preserving the ritual function such images obtain in historic and contemporary urban performances. “The Epic of the Martyr,” Al-Bahloly explained, “re-staged in the artwork the pathos that the mourning rituals aroused.” Mourning, as a lamentation speech, opens a space between legal and revolutionary action which effectively opens “a horizon of justice.”

Following Ramadan, Saleem Al-Bahloly’s talk “The Resurrection of Tradition, or A Critical Theory of the Artwork in the Postcolonial World” explored the rhetorical function of mourning demonstrated in Kadhim Hayder’s series, The Epic of the Martyr (Fig. 2). Al-Bahloly spoke of the artist’s ritual imagery, namely his evocative horses, as preserving the ritual function such images obtain in historic and contemporary urban performances. “The Epic of the Martyr,” Al-Bahloly explained, “re-staged in the artwork the pathos that the mourning rituals aroused.” Mourning, as a lamentation speech, opens a space between legal and revolutionary action which effectively opens “a horizon of justice.”

Lastly, miriam cooke spoke of the cultural production of revolutionary Syria in “Curating the Syrian Revolution.” cooke described artists as “filling the vacuum” at a time when much of the world seems to have turned its back to the prolonged humanitarian crisis. cooke described instances of “Creative Resistance” and “Creative Memory,” the latter emphasizing the curation of a website, The Creative Memory of the Syrian Revolution, launched by graphic designer Sana Yazigi. The site provides a vital platform for responding immediately to political events, capturing and disseminating often fleeting physical works—like graffiti. Moreover, cooke explained, the site allows artists and visitors to shape individual, revolutionary, and aesthetic identities.

All speakers joined together for a final discussion led by Pamela Franks. Davies and Seggerman emphasized the importance of working transnationally within museum departments, as well as a disciplinary willingness—as touched upon by Komaroff—to question geographic borders and historical chronologies. “The engagement of cosmopolitan sites and cities at different historical moments will hopefully prevent,” Rizvi noted, “the danger of the Middle East becoming a monoculture.” Al Qassemi and cooke suggested that such engagement increasingly look to the digital as a site of dissemination. There, it seems, the historical methodologies of entanglement and synchronicity find a contemporary complement.

Written by Alejandro Nodarse, History of Art, B.A./M.A.