Harold Hongju Koh: "A National Security Impeachment"

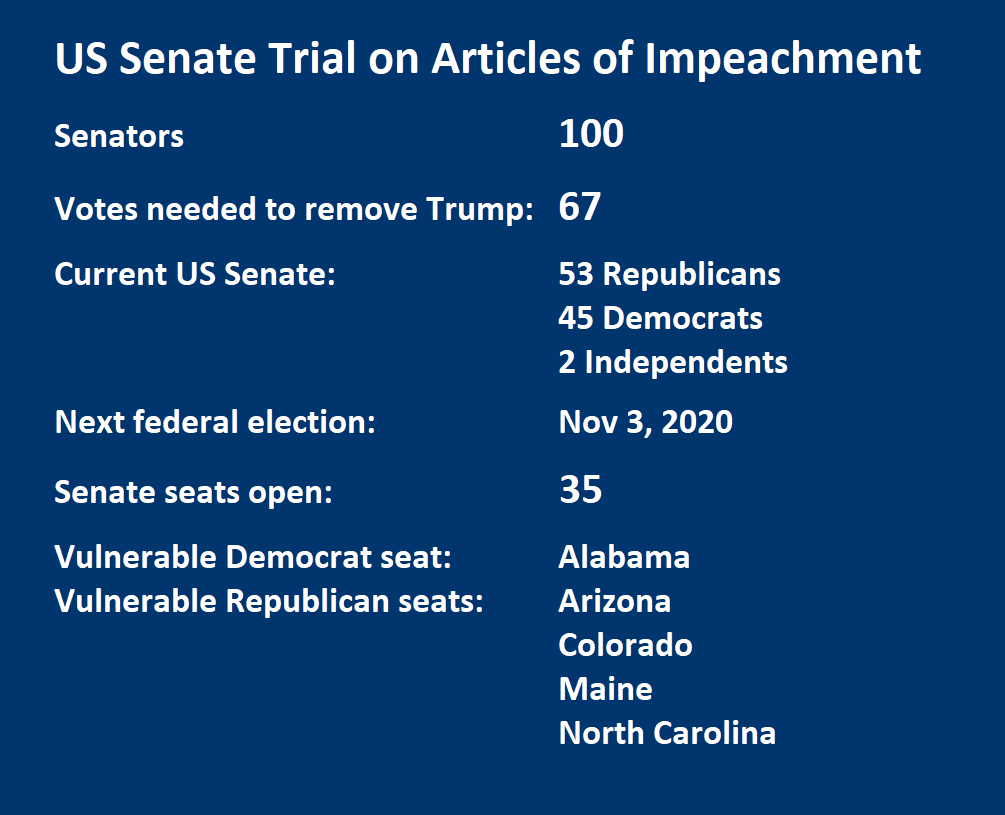

The House of Representatives proceeds to impeach Donald Trump, the first presidential impeachment in US history for national security offenses. The Senate won’t remove him from office, but the proceedings have laid bare the severe national security distortions caused by his unconstitutional misbehavior.

The Articles of Impeachment voted by the House narrowly claim abuse of power and obstruction of Congress. At this writing, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has committed to hold an impeachment trial. Less clear is whether or how Trump plans to defend. What makes prediction hazardous is that two radically different impeachment processes are unfolding. The Democrats claim that President Trump welcomed foreign interference in the tight 2016 election and, after Special Counsel Robert Mueller declined to charge criminal misconduct, brazenly sought foreign interference to denigrate his leading 2020 rival. When Congress investigated, he stonewalled subpoenas until they became irrelevant. Yet Trump’s base largely embraces the Republican counternarrative: that he is blameless and persecuted after prevailing in the 2016 presidential election despite the interference of Democrats and corrupt Ukrainians. Each side gambles that its narrative will gain steam, forcing the other side to weaken politically.

.png)

Bill Clinton’s trial lasted five weeks; McConnell seems to favor two. Some Republicans favor a longer trial, reckoning it could weaken Democratic senatorial presidential candidates. Yet an extended trial – perhaps with new Republican witnesses – risks growing public doubt about Trump that could sway shaky Republicans to side with impeachment. Even then, since the Democrats will fall many votes short of the 67 needed for conviction and removal, Trump will stay president until at least January 2021. So what does his impeachment really mean?

Strangely lost in the impeachment drama has been the Articles’ core message: that “President Trump used the powers of the Presidency in a manner that [1] compromised the national security of the United States and [2] undermined the integrity of the United States democratic process.” Trump is being impeached not just because he is a bad president, but because he is a glaring national security threat, who has sought to normalize both election insecurity and an extreme form of executive unilateralism.

These threats are deeply interconnected. Free and fair elections are the lifeblood of US constitutional democracy. Yet when asked whether he would again accept derogatory foreign opposition research, Trump responded that of course he would look to see if it served his personal political benefit. Since 2013, Russia has conducted nearly 40 election influence campaigns targeting 19 countries, and Mueller and other senior US intelligence officials have confirmed that Russia again is poised to influence the 2020 elections.

Election tampering is most virulent when it undemocratically prolongs in office a leader who endorses extreme executive unilateralism. The Reagan and George W. Bush administrations trumpeted extreme executive power as a defining feature of their constitutional vision. Afflicted by weak legislative support, the Clinton and Obama presidencies resorted to ad hoc unilateralism to respond to particular national security crises. But under Trump’s presidency, executive unilateralism has reached crisis levels. Until now, constitutionalists could assume that each president had some internalized limit where public duty or shame would dictate self-restraint. But Trump has displayed unique contempt for constitutional checks and balances, fueled by his conviction that “Article II [of the Constitution] allows me to do whatever I want.”

The systemic way to understand the Trump impeachment is as a thoroughgoing assault on what three decades ago I called “The National Security Constitution,” the substructure of US constitutional norms that protect the operation of checks and balances in national security policy. As Justice Robert Jackson famously wrote, “[p]residential powers are not fixed but fluctuate, depending upon their disjunction or conjunction with those of Congress,” with the legality of executive action reviewable by the courts. But when modern national security threats arise, weak and strong presidents alike have institutional incentives to monopolize the response; Congress has incentives to acquiesce; and courts have incentives to defer, creating an interactive dysfunction that disrupts the constitutional norm that US national security policymaking should be a power shared.

Under Trump, this institutional dysfunction has reached dangerous heights. His extreme unilateralist campaign has exploited both the eagerness of the Republican Senate to normalize his behavior and the impulse of a Supreme Court on which he has filled two seats to defer to imagined claims of national security necessity. So, this same president who bizarrely declared Canada to be a “national security threat” has invoked phony national security “emergencies” to act unilaterally in such traditional congressional areas as immigration, warfare, trade, international agreements and the power of the purse. He has claimed flimsy national security justifications to impose a travel ban on Muslim-majority countries, build a wall that Congress refused to fund, separate infants from their parents at the border, condone torture, expel transgender individuals from the US military and impose tariffs on allies under old trade laws. When blocked in court, he has reached for increasingly illegal solutions, denigrating judges even while aggressively filling the bench with executive-power advocates. And in William Barr, Trump has found an attorney general constitutionally committed, as one Republican put it, to “using the office he holds to advance his extraordinary lifetime project of assigning unchecked power to the president.”

This historical march toward unilateral presidentialism could slow if the next administration were to strongly push the pendulum the other way. Instead, the Democrats’ persistent political response has been to under-correct, increasingly exposing more US constitutional democracy to existential threat. Elsewhere, I have chronicled the many “resistance measures” taken to challenge the Trump administration’s illegal initiatives through “transnational legal process.” But we cannot restore constitutional equilibrium simply by “throwing these rascals out.” After Watergate’s malicious domestic election tampering, a bipartisan Congress enacted stiffer laws regarding campaign conduct and finance. To address the foreign policy dysfunction of Vietnam, Congress also passed national security “framework statutes” to constrain war powers, adding intelligence oversight, emergency economic powers and international agreement-making.

Trump’s impeachment presents a similarly rare window to consider how the constitutional system can respond to the twin threats of electoral insecurity and executive unilateralism. To prevent these twin threats from becoming the new normal, the nation needs a broader package of forward-looking responses from both private and public actors.

To address election insecurity, Congress should enact the Foreign Influence Reporting in Elections, or FIRE Act, and Duty to Report Act, two bipartisan bills that impose sanctions on any entity that attacks a US election. Because handmarked paper ballots remain most secure and cost-effective, better election security means going back to the future: to modern domestically produced machines; backup paper ballots and optical scanners less vulnerable to foreign interference; and election infrastructure disconnected from the internet. Most of these changes could be implemented simply by the Senate passing a third law already passed by the House: the Securing America’s Federal Elections, or SAFE Act. Foundation officials and cyberexperts must identify technologies that enable social media to drive voter preferences. And the Democratic presidential candidates should issue a joint statement calling election insecurity a virulent national security threat that merits “zero tolerance.”

More broadly, Congress must tackle the greater national security threat of executive unilateralism, which has now gutted core legislative prerogatives. The House should consider proposals for new national security framework legislation to guide interbranch conduct to end the Forever War, restore Congress’s power over international trade, repeal the travel ban and limit executive power to reprogram appropriations. New legislative mechanisms must regulate the use of statutory emergency powers, use of force in Iran or Yemen or against emerging terrorist groups, and withdrawal from vital international agreements like NATO and the WTO. To level the playing field with the executive, Congress must create stronger central repositories of national security expertise and legal advice, forbid the practice of secret agency legal opinions, and require their confidential submission to the relevant select committees. And Trump’s impeachment graphically shows the need for Congress to strengthen internal checks and balances by enacting stronger legal protections for whistleblowers determined to obey their constitutional oaths against lawless senior officials.

Of course, most of these reforms are not politically achievable until 2021 and so fall to future leaders. If impeachment publicity forces McConnell to bring the long-delayed election security bills to the Senate floor, they could be adopted earlier.

What Trump’s impeachment teaches is that America’s National Security Constitution will not protect itself. An even graver national security threat than electoral interference is the one posed by licensing nakedly unilateralist presidents like Trump. Trump’s extreme contempt for the rule of law demands an equally ambitious counter-agenda to avoid under-correction. We cannot prevent the next catastrophe without defining and implementing a coherent menu of politically achievable acts for corrective national security reform.

Harold Hongju Koh is Sterling Professor of International Law, Yale Law School; Legal Adviser, U.S. Department of State (2009-13); Assistant Secretary of State for Democracy, Human Rights & Labor (1998-2001).

This article was co-published with Just Security and published December 17, 2019.