An extinct language finds a new audience at Yale

A recent workshop on an extinct and very rarely studied language opened a “brand new door to fresh historical perspectives” for Yale graduate student Yuan Chen.

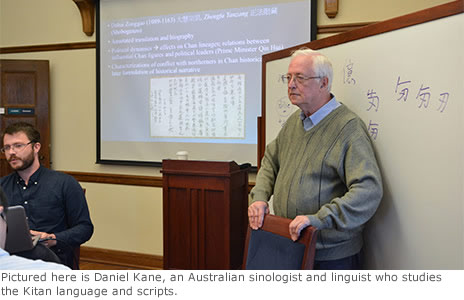

Chen, who studies medieval Chinese history, participated in the Kitan Language Workshop, which presented her with a “once-in-a-lifetime opportunity” to learn about theancient language developed by the Kitan people. The workshop, which took place May 11-19, was organized by Valerie Hansen, professor of history at Yale, and funded by the Council on East Asian Studies in the Whitney and Betty MacMillan Center for International and Area Studies at Yale, and the Edward J. and Dorothy Clarke Kempf Memorial Fund. It was led by Daniel Kane, an Australian sinologist and linguist who has spent more than a decade on the study of the Kitan language and scripts.

Between the 10th and 12th centuries, the nomadic Kitan dominated a large swath of Mongolia and Manchuria and created the Liao Dynasty, a rival to China’s Song Dynasty. The Kitans, who were the first people to make Beijing one of their capitals, originally did not have their own writing system. After the founding of their empire, the Kitans saw the need to invent their own script to define the Kitan identity. They created two scripts by borrowing from the Chinese and Uighur languages.

“It is fascinating to learn about how these ancient peoples used language to define their ethnic identity and for empire building,” notes Chen.

“It is fascinating to learn about how these ancient peoples used language to define their ethnic identity and for empire building,” notes Chen.

The workshop, which was attended by six Yale affiliates and 11 participants from around the world, was an eight-day “crash course,” says Hansen. “Our goal with the workshop was to build a cohort of people who are going to continue to study the Liao dynasty and learn to read the Kitan inscriptions.”

Part of Chen’s graduate research focuses on the conquest dynasties in China founded by nomadic peoples such as the Kitans and the Mongols. “The Liao Dynasty invented a unique government system to manage a multi-ethnic population and left a rich legacy in Chinese and Inner Asian politics and cultures. It established itself as a successful, exemplary steppe empire that the Mongol Empire was later modeled on. I hope learning its language can help me better understand this little-known but important medieval Asian empire.”

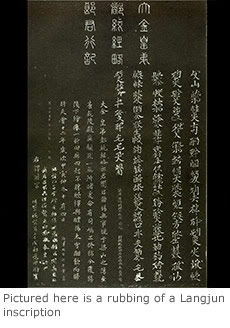

Chen says that the work done during the workshop was akin to a “detective story” in which information was pieced together from fragmented evidence from different stele inscriptions, epitaphs, and engravings on mirrors or coins. “It was exciting to learn about how the graphs are deciphered,” she notes.

Chen says that the work done during the workshop was akin to a “detective story” in which information was pieced together from fragmented evidence from different stele inscriptions, epitaphs, and engravings on mirrors or coins. “It was exciting to learn about how the graphs are deciphered,” she notes.

“Being here at Yale has been remarkable for me,” says Kane, who recently wrote a book on the Kitan language that he hopes will be a catalyst for further research. “There are only nine or ten people in the field in the West who study this topic, and not many more in Asia. Most of us in the field are in our 60s, 70s, and 80s. We hope the younger generation will continue to study this language; otherwise it will just disappear again.”

“The Kitan people are an unexplored chapter in Chinese history and a particularly congenial chapter for non-Chinese historians,” says Hansen. “By studying the Liao dynasty, we can add to the record of Chinese history.”

“This intense workshop allows me to use an entirely new genre of primary sources in a previously poorly understood language in my research. It not only makes it possible for us to read some of the extant Kitan texts, but also creates the opportunity that participants of this workshop can work together in the future to make more breakthroughs in deciphering Kitan,” says Chen.

The Council on East Asian Studies at the MacMillan Center serves as Yale’s interdisciplinary hub for the study of all aspects of East Asia and its constituent peoples, cultures, and societies. For over 50 years, it has promoted education about East Asia both in the Yale curricula and through lectures, workshops, conferences, film series, cultural events, and other educational activities open to students, faculty, and the general public. With nearly 30 core faculty and 20 language instructors spanning 10 departments on campus, East Asian studies is one of Yale’s most extensive area studies programs.

Written by Bess Connolly Martell, Office of Public Affairs & Communications