In Ottoman Turkish manuscripts, Yale students find delicious mysteries

Since last summer, Ozgen Felek has passed many illuminating hours in the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library’s reading room poring over Yale’s collections of Ottoman Turkish manuscripts, which are uncatalogued and little studied.

The 568 manuscripts are stored inside nondescript boxes. For Felek, a scholar of Ottoman language and culture, opening the boxes was like unwrapping hundreds of gifts.

“It was heaven,” she said.

Felek, a lector in Ottoman Turkish in Yale’s Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, incorporated the manuscripts into “Reading and Research in Ottoman History and Literature,” a course she taught this fall. Each of her 10 students — seven graduate students and three undergraduates — chose a manuscript to research.

“I wanted my students to have the opportunity to study Ottoman Turkish in the context of these fascinating sources,” said Felek, a native of western Turkey and an accomplished artist of Islamic illumination and miniature painting. “Their work has enhanced our understanding of the manuscripts and I’m deeply impressed by what they discovered.”

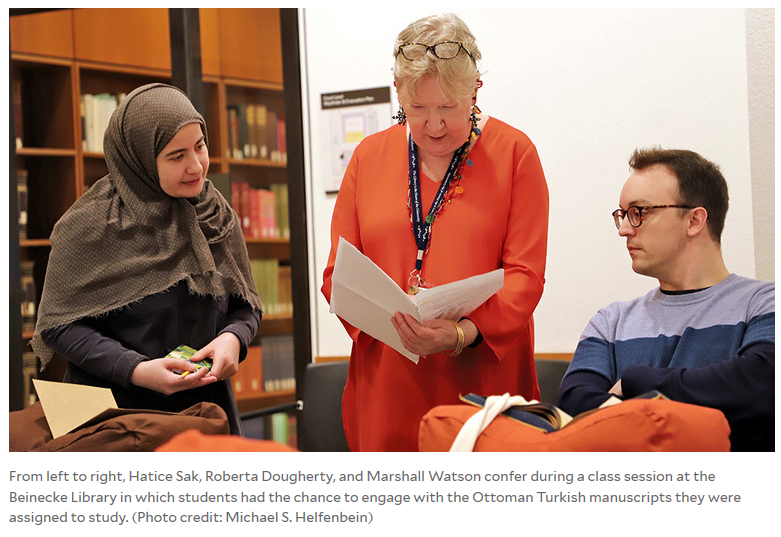

The students personally engaged with the manuscripts during multiple class visits to the Beinecke, examining their handwritten text and materiality — the inks, paper, and covers, for instance. They photographed the pages to facilitate research outside the library. And they unraveled mysteries and shared their findings at a symposium sponsored by the Council on Middle East Studies on Dec. 11 at Sterling Memorial Library, which Felek organized with Roberta Dougherty, Sterling’s librarian for Middle East studies.

Heavily influenced by Arabic, Ottoman Turkish was used within the Ottoman Empire, which ruled much of Southeast Europe, Western Asia, and Northern Africa for nearly 700 years, from 1299 to 1923, as well as during the early years of the Turkish Republic that rose from the empire’s collapse. Yale’s collection of Ottoman Turkish manuscripts formed gradually, beginning in 1870 when Edward Salisbury, Yale’s first professor of Arabic and Sanskrit languages and literature, donated his library of Arabic, Persian, and Ottoman Turkish manuscripts to the university.

The manuscripts date from the mid-15th century to the early-20th century. Held in three distinct collections, they encompass 19 genres, including history, poetry, mysticism, Islamic law, religious sermons, and dictionaries, Felek said.

Matthew Dudley, a Ph.D. student in history, studied Turkish MSS 25, a manuscript listed as “an untitled memoranda book of a merchant.” His research led him to propose that the manuscript is misidentified. Likely created in Algeria, it records a series of payments from roughly 1809 to 1814 in connection with a wide range of entities, including shops, bathhouses, hotels, warehouses, and bakeries, Dudley explained.

Dudley posited that the manuscript is a register connected to a system of taxation or a waqf foundation — a charitable organization under Islamic law — pointing out that the payments are recorded in a highly predictable bi-annual manner, which seems inconsistent with the typical fluctuations of business activity.

Fatos Karadeniz, a senior majoring in molecular, cellular and developmental biology, studied Turkish MSS Supplement 6, a medical guide to herbal remedies originally written by Muhammed bin Ali between 1689 and 1690. Yale’s version is estimated to date to the mid-18th century.

The manuscript’s first section features illustrations of medicinal plants — such as St. John’s wort, wild asparagus, and bird’s nest fern — instructions for preparing them, and explanations of the diseases and symptoms they could treat. The second section is a glossary that translates medical terms in Italian, Arabic, and Ottoman Turkish, and the third section consists of charts matching symptoms to relevant treatments, Karadeniz explained.

“Muhammed bin Ali’s primary goal was to make this information accessible to people who lived in the Ottoman Empire, as Europeans would come to markets and sell these plants and remedies at much higher prices,” she said.

Karadeniz noted that the manuscript’s entry for St. John’s wort, which people today use to treat mild depression, advises that the plant can “strengthen nerves,” although she was not certain whether this referenced physical nerves or temperament.

“At the end, it was noted that only a competent physician should use this plant because it’s so strong and that beginners should absolutely not touch it,” she said.

Eda Uzunlar, a sophomore political science major and first-generation Turkish immigrant, examined the tiniest of the manuscripts: a 4.6 cm by 7.5 cm “untitled booklet on magic and prayers.” The booklet’s date and author are unknown, Uzunlar explained.

“It’s like a little book of mystery,” she said.

The booklet’s author provides readers two versions of prayers — one to recite, and one to wear pinned to their clothing — covering an eclectic mix of concerns. There are prayers for curing headaches, and talismans for preventing bad luck, tying the tongues of one’s enemies, and becoming cuter, said Uzunlar.

She expressed gratitude to Felek, Dougherty, and her classmates for their work.

“This class and this little booklet offered me a little piece of culture and history that I wasn’t aware of before,” Uzunlar said.

Written by Mike Cummings for YaleNews.